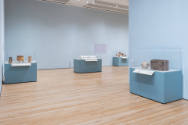

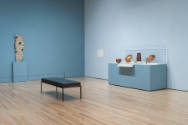

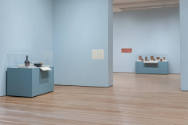

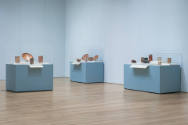

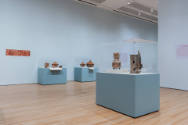

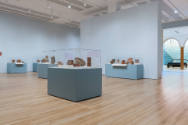

Forces of Nature: Ancient Maya Art from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Sunday, August 27, 2023 - Sunday, January 7, 2024

For the ancient Maya, the natural world was both a source of nourishment and danger. From the sun to wildlife to maize crops, forces of nature manifested supernatural beings that were inseparable from their lives. This exhibition explores the rich world of the supernatural in ancient Maya art, through 200 works from LACMA’s notable collection — including ceramic vessels and figurines, and greenstone jewelry from present-day Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras. These ancient artworks showcase how artists portrayed the supernatural world and how royalty acquired and displayed their own supernatural power.

The Blanton presentation is organized by Rosario I. Granados, Marilynn Thoma Associate Curator, Art of the Spanish Americas

Forces of Nature: Ancient Maya Art from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Support for this exhibition at the Blanton is provided in part by Bettye Nowlin.

Gallery TextThe Blanton presentation is organized by Rosario I. Granados, Marilynn Thoma Associate Curator, Art of the Spanish Americas

Forces of Nature: Ancient Maya Art from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Support for this exhibition at the Blanton is provided in part by Bettye Nowlin.

Forces of Nature and the Maya cosmos

The Maya, who had lived for millennia in what today is Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, El Salvador, and Honduras, believed that the forces of nature—such as the sun, rain, and lightning—as well as fruits of the earth—like maize or cacao—were supernatural entities whose relationships mirrored natural cycles and mimicked human bonds. Based on the idea that the natural world was a source of both nourishment and danger, artists during the Classic period (250–950 CE) visualized these beings in human or animal form to communicate and negotiate with them.

Maya kings and queens, along with their royal courts, made offerings to ancestors and other supernatural entities, but also interacted with them in multifaceted ways. Rulers took the names of forces of nature—like K’inich Ajaw (Sun-Faced Lord)—and dressed as them in ceremonies and dances. After death, ancestors transformed into those same natural powers, reborn as the diurnal sun or the Maize God. In ritual ceremonies and pictorial narratives, the actions of humans and supernatural entities replicated one another, illustrating that both worlds were effectively inseparable.

The artworks in this exhibition are objects through which the Maya interfaced with one another and with divine forces that interacted in a universe believed to be a threefold unit, composed of the underworld, the celestial realm, and the earth. This world of the living was divided into four quadrants, organized according to the cardinal directions. Although the focus of this show is on Maya art, select pieces from the Olmec, Zapotec, and Aztec culture are also present to demonstrate the extensiveness of similar concepts throughout the cultural region today known as Mesoamerica. All works are part of the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

Supernatural Entities of Sky, Earth, and the Underworld

The Maya concept k’uh, often translated as god or deity, refers to a sacred essence or entity that was generally associated with one of the three cosmic realms of sky, earth, or the underworld. The word k’uhul was used to refer to people embodying those divine forces, to buildings where they lived, or to diverse artifacts that received that spiritual energy.

Since the worlds of humans and sacred essences mirrored and overlapped each other, artists illustrated the vast array of Maya deities with human and animal characteristics, often portraying them performing daily-life activities. Visual clues, ranging from spiral or squared pupils, to mirror signs on their skin, signal the supernatural nature of divine characters. However, it can be challenging to identify these different divine entities, since they could have multiple manifestations and exist in pairs or groups of four, each with different colors and characteristics in alignment with the Earth’s quadrants, determined by the cardinal points that give structure to the cosmos. They could also merge, taking on the physical characteristics and powers of others. These divine entities were believed to move throughout the cosmos on a daily or annual basis, or during conjuring rituals.

Animals in Maya Art and Religion

Narratives included in both Maya art and the sixteenth-century compilation of stories known as the Popol Wuj emphasize the shared origins of humans and animals, presenting them in conflict or cooperation with each other. Some artistic depictions show animals in unusual or humorous situations. Others compare humans to monkeys, thereby accentuating their similarities. No matter the context, animals regularly move across realms of the universe, traversing different environments, always creating links between them.

Animals were also associated with practices of ritual transformation. The Maya nobility related to animals by adopting their names. In order to adopt characteristics of those same animals, they also wore costumes and headdresses adorned with the resplendent feathers of the quetzal bird, or jewelry made of shells from rivers or the sea. Jaguars, in particular, were admired and feared for their strength and role as stealthy predators. For this reason, they were a symbol of war and social status, and were exploited to show political and spiritual power.

Divine Rites of Kings and Queens

Natural forces have the power to nurture communities. Yet, they can also be destructive. The Maya invoked them to engender both reverence and fear through rituals that were key for maintaining the balance of the cosmos, but also for displaying their leader’s own power. Rulers took on names of deities and impersonated them. Especially prominent were the names of solar and lightning deities, evident in the title K’inich (Sun-Faced), assumed by Palenque rulers, and Sihyaj Chan K’awiil (Sky-Born K’awiil) from Tikal. Nobility also owned effigies of divine entities to witness their actions, and thereby endorse their rule. They also made calendrical calculations to link themselves with the births and actions of the gods.

Las fuerzas de la naturaleza y el cosmos maya

Los mayas, que han vivido durante milenios en lo que hoy es Guatemala, México, Belice, El Salvador, y Honduras, creían que las fuerzas de la naturaleza —como el sol, la lluvia, y el relámpago— así como los frutos de la tierra —como el maíz o el cacao— eran entidades sobrenaturales cuyas relaciones reflejaban los ciclos naturales e imitaban los vínculos humanos. A partir de la idea de que el mundo natural era una fuente tanto de sustento como de peligro, los artistas del período clásico (250-950 e. c.) visualizaron a estos seres con forma humana o animal para poder comunicarse y negociar con ellos.

Los reyes y las reinas mayas, junto con sus cortes reales, ofrecían ofrendas a sus ancestros y otras entidades sobrenaturales, pero también interactuaban con ellos en maneras multifacéticas. Los soberanos adoptaban los nombres de las fuerzas de la naturaleza, como K’inich Ajaw (Señor del Rostro Solar), y se vestían como ellas en ceremonias y bailes. Después de su muerte, los ancestros se transformaban en esos mismos poderes naturales y renacían como el sol diurno o el dios del maíz. En ceremonias rituales y en narraciones pictóricas, las acciones de los humanos y las entidades sobrenaturales se replicaban mutuamente, lo que muestra que ambos mundos eran efectivamente inseparables.

Las obras de arte en esta exposición son objetos que los mayas usaban para interactuar entre ellos y relacionarse con las fuerzas divinas que actúan en el universo, al cual entendían como una unidad triple compuesta por el inframundo, el reino celestial y la tierra. El mundo de los vivos estaba dividido en cuatro cuadrantes, organizados de acuerdo a los puntos cardinales. Aunque el arte maya es el eje central de esta muestra, también se incluyen obras selectas de las culturas olmeca, zapoteca y azteca para mostrar cuán similares eran ciertos conceptos dentro de la región cultural hoy conocida como Mesoamérica. Todos estos objetos artísticos son parte de la colección del Museo del Condado de Los Ángeles (LACMA, por sus siglas en inglés).

Las entidades sobrenaturales del cielo, la tierra y el inframundo

El concepto maya k'uh, que suele traducirse como “dios” o “deidad”, hace referencia a una esencia o entidad sagrada que por lo general, se asociaba a uno de los tres reinos cósmicos del cielo, la tierra o el inframundo. La palabra k'uhul se utilizaba para referirse a las personas que encarnaban esas fuerzas divinas, a los edificios donde vivían o a diversos artefactos que recibían energía de ellas.

Dado que los mundos de los humanos y las esencias sagradas se reflejaban y superponían entre sí, los artistas ilustraban la amplia variedad de deidades mayas con características humanas y animales, soliendo representarlas realizando actividades de la vida diaria. La esencia sobrenatural de los personajes divinos elementos se representaba a través de códigos visuales, que abarcaban desde pupilas en espiral o cuadradas hasta símbolos de espejos en la piel. Sin embargo, identificar estas diversas entidades divinas puede resultar una tarea compleja, ya que ellas tendían a manifestarse de múltiples maneras y existir en pares o grupos de cuatro con colores y características diferentes según los cuadrantes de la Tierra, determinados por los puntos cardinales que estructuran al cosmos. A veces, también podían fusionarse y adoptar las características físicas y los poderes de otros seres sagrados. Se creía que estas entidades divinas podían moverse por el cosmos todos los días, una vez al año, o durante los rituales de invocación.

Los animales en el arte y la religión maya

Las narraciones incluidas tanto en el arte maya como en la compilación de historias del siglo XVI conocida como el Popol Wuj hacen hincapié en los orígenes compartidos de los humanos y los animales, presentándolos en conflicto o en cooperación entre sí. En algunas representaciones artísticas, se muestran animales en situaciones inusuales o humorísticas. En otras, se compara a los humanos con los monos, acentuando sus similitudes. Sin importar el contexto, los animales solían desplazarse entre las distintas áreas del universo, atravesando así diferentes entornos y creando conexiones entre ellos.

Los animales también se asociaban con prácticas de transformación ritual. La nobleza maya se relacionaba con los animales adoptando sus nombres. Con el objeto de adoptar características de esos animales, también solían vestir trajes y tocados adornados con las resplandecientes plumas del pájaro quetzal, o joyas de conchas de ríos o del mar. Los jaguares, en particular, eran admirados y temidos por su fuerza y rol de depredadores sigilosos. Por esta razón, constituían un símbolo de guerra y estatus social, y eran explotados para mostrar poder político y espiritual.

Los ritos divinos de los reyes y las reinas

Las fuerzas naturales tienen el poder de sustentar comunidades. Sin embargo, también pueden ser destructivas. Los mayas las invocaban para provocar tanto la veneración como el miedo mediante rituales que eran fundamentales para mantener el equilibrio del cosmos y exhibir el poder de sus líderes. Los soberanos adoptaban nombres de deidades y las imitaban. Los nombres de las deidades solares y de los rayos eran los más prominentes, como se evidencia en el título K'inich (Rostro Solar) que adoptaron los reyes de Palenque y Sihyaj Chan K'awiil (K'awiil Nacido en el Cielo) de Tikal. Los miembros de la nobleza también eran dueños de efigies de entidades divinas para que fueran testigos de sus acciones y, de esta manera, respaldaran su gobierno. Además realizaban cálculos calendáricos para establecer vínculos con los nacimientos y las acciones de los dioses.