The Floating World: Masterpieces of Edo Japan from the Worcester Art Museum

Sunday, February 11, 2024 - Sunday, June 30, 2024

Enjoy more than 130 woodblock prints and painted scrolls from one of history’s most vibrant artistic eras.

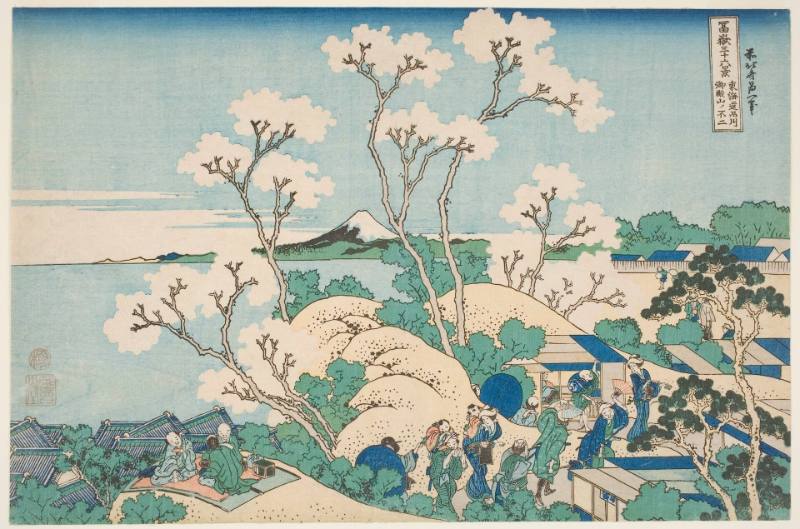

After centuries of conflict and war, Japan’s Edo period (1603–1868) was a time of peace, stability, and economic growth. Members of the ruling class patronized artists, merchants, entertainers, and courtesans in major cities like Tokyo (then called Edo), Kyoto, and Osaka. Sharing a visual culture and appreciation for the transient pleasures of life, such diverse groups comingled in a metropolitan melting pot known as ukiyo, or “floating world.” There, a new art genre emerged: Ukiyo-e. These “pictures of the floating world” depict the lifestyle, pleasures, and interests of the urban population— from samurais, geishas, and kabuki actors to boat parties, palaces, and lush landscapes.

Not to be missed, this presentation marks the first time the Worcester Art Museum is touring its famed collection of Japanese artworks.

This exhibition is organized by the Worcester Art Museum with support from the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation.

Generous funding for this exhibition is provided in part by The Freeman Foundation.

Gallery TextAfter centuries of conflict and war, Japan’s Edo period (1603–1868) was a time of peace, stability, and economic growth. Members of the ruling class patronized artists, merchants, entertainers, and courtesans in major cities like Tokyo (then called Edo), Kyoto, and Osaka. Sharing a visual culture and appreciation for the transient pleasures of life, such diverse groups comingled in a metropolitan melting pot known as ukiyo, or “floating world.” There, a new art genre emerged: Ukiyo-e. These “pictures of the floating world” depict the lifestyle, pleasures, and interests of the urban population— from samurais, geishas, and kabuki actors to boat parties, palaces, and lush landscapes.

Not to be missed, this presentation marks the first time the Worcester Art Museum is touring its famed collection of Japanese artworks.

This exhibition is organized by the Worcester Art Museum with support from the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation.

Generous funding for this exhibition is provided in part by The Freeman Foundation.

Introduction

The Edo period (1603–1868) ushered in an era of peace and prosperity after centuries of political and military conflict in Japan. With no wars to be waged, the samurai (members of the ruling warrior class) established themselves in major cities like Tokyo (then called Edo), Kyoto, and Osaka, where they patronized artists, merchants, entertainers, and courtesans. They all mingled in what was known as the ukiyo, literally “the Floating World,” an urban culture in which the arts, popular entertainment, and extravagant expenditure flourished.

The Edo period (1603–1868) ushered in an era of peace and prosperity after centuries of political and military conflict in Japan. With no wars to be waged, the samurai (members of the ruling warrior class) established themselves in major cities like Tokyo (then called Edo), Kyoto, and Osaka, where they patronized artists, merchants, entertainers, and courtesans. They all mingled in what was known as the ukiyo, literally “the Floating World,” an urban culture in which the arts, popular entertainment, and extravagant expenditure flourished.

For more than two and a half centuries, artists designed ukiyo-e (pictures of the Floating World) that drew on classical art, literature, and popular design to create prints and paintings of the urban population’s leisure activities. Before the eighteenth century, woodblock printing in Japan primarily reproduced written texts; printed images were usually either black and white or hand colored. The new technology popularized by master printer Suzuki Harunobu in 1765 allowed the production of polychrome prints, in which a separate carved block was used for each color, sometimes up to twenty per image. The subject matter of these prints gradually expanded during this period from courtesans, Kabuki actors, and other features of the urban scene to include vibrant and expressive images from folktales, Buddhist motifs, fashions, the natural world, and historical events.

The more than 130 prints and paintings on view in The Floating World: Masterpieces of Edo Japan, primarily drawn from the illustrious John Chandler Bancroft Collection at the Worcester Art Museum, span the entire history of the ukiyo-e genre, capturing its diversity in terms of size, date, material, function, content, and style. These extraordinary works testify to the artistic skill and vision of the designers and printmakers of early modern Japan.

Origins of Ukiyo

Origins of Ukiyo

The word ukiyo originally referred to the Buddhist idea of the impermanence of life. Its meaning transformed during the Edo period when the character meaning “transitory” was replaced by a homonym (word spelled or sounding the same but signifying something different) meaning “to float.” War-weary townspeople who joked about finding solace in entertainment rather than in religion celebrated the hedonism and sensuality of the “Floating World.” The ethos of the Floating World is best captured in the 1661 publication Ukiyo Monogatari (Tales of the Floating World) by Asai Ryōi:

Living only for the moment, savoring the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms, and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking sake, and diverting oneself just in floating, unconcerned by the prospect of imminent poverty, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried along with the river current: this is what we call ukiyo.

The Production of Woodblock Prints

Most of the works in this exhibition were produced using the process of mokuhanga, woodblock printing. In its most basic form, this technique consisted of transferring and carving a design into a woodblock, usually made of durable cherrywood. The printmaker then applied ink to the raised lines of the design, placed a piece of paper on top, and used a smooth, disk-shaped object called a baren to press the ink onto the paper. To incorporate multiple colors into the same work, an artist carved separate woodblocks, each one printing the individual elements of the design in a specific color.

Blocks could be reused many times, and the printmaker could make slight adjustments to the design by carving away or altering parts of the image. In some cases, blocks were reprinted many years after their initial publication. Print production typically involved collaboration between a designer, carver, printer, and publisher.

While the size and shape of Japanese prints may vary widely, paper dimensions in the Edo period were regulated. Below are three of the standardized print sizes on view in these galleries:

Oban (15 x 10 in): This was the most common size for ukiyo-e prints. A design could incorporate two to three sheets (horizontally or vertically), allowing the artist to create diptychs and triptychs.Hosoban (13 x 5.5 in): This rare and narrow print size was most often used for yakusha-e (actor prints) during the eighteenth century and kacho-e (bird and flower prints) during the nineteenth century.Hashira-e (27 x 5 in): Also known as "pillar pictures,” this long and thin format was popularized around the turn of the eighteenth century and was an alternative to more costly painted scrolls, which could be hung in the alcoves of houses.

Entertainment

As Japan entered the Edo period, the daimyō (feudal rulers), fought for power. At the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated his enemies in a decisive victory, and soon established the Tokugawa Shogunate (military government). A long and largely peaceful era ensued, allowing the residents of Japan’s main cities to pursue entertainment, rather than wage war.

Most cities of this period were home to flourishing theaters, brothels, and shopping districts that welcomed clients of all kinds. The public calendar was also packed with festivals, holidays, and parades. Revelry became an essential component of urban life. Entertainment venues enjoyed the patronage of the wealthiest members of society, the daimyō and their samurai retainers (who were required to reside in Edo and pay court to the shogun for part of each year), as well as the middle classes—many of whom were merchants who had prospered by providing goods and services to urban inhabitants. The various characters and activities of this vibrant environment feature among the earliest and most quintessential subjects in ukiyo-e.

Poetic Pictures

Literature flourished in Japan during the Edo period, and this partly reflected the high rate of literacy among the chōnin (townspeople). Composing poetry, mastering calligraphy, and letter writing were a part of everyday life for almost everyone, regardless of social class. Classical texts, formerly only available to aristocrats, and books of contemporary literature were produced in great quantities using new techniques in woodblock printing and were widely circulated. Soon, printed books were accompanied by pictures, and their subjects expanded to include travel guides, religious texts, political commentaries, art-historical treatises, self-help books, essays, satires, and picaresque fiction.

Ukiyo-e drew from this vast and growing literary canon to illustrate scenes that spoke to the daily experiences of those in the Floating World. Single-sheet prints and illustrated books relied on an audience capable of interpreting subtle visual clues about their themes and narratives. Stylistically, these images mirrored the population of the ukiyo in many ways, merging aristocratic visual language with design traditions associated with the lower classes and the townspeople.

Landscape and the Natural World

Images of birds, flowers, and other elements of the natural world have long been integral to the arts of Japan, perhaps in response to the variety and beauty of this island nation’s landscape. Indigenous Shinto practices—based on animist beliefs in nature spirits—as well as Buddhist ideas about impermanence and the connectedness of all living things contribute to this delight in images of nature. In the more urban culture developing during the Edo period, the inherent changeability of nature resonated with the ethos of the Floating World, which centered on life’s transient pleasures. Ukiyo-e artists sought to capture the momentary beauty of their subjects and often focused on the passage of seasons, the blooming of flowers, and fleeting glimpses of animals. Images featuring the landscape around the capital city of Edo and famous sites along Japan’s main travel routes were also highly popular.

Bijin-ga: Pictures of Fashionable Beauties

Bijin typically refers to the beautiful young women in pictures of the Floating World. These generally showed fashionably dressed women, often courtesans, their faces and figures embodying the ideal beauty standards of the time. Such glamorous images concealed the harsh realities of the daily lives of courtesans in the red-light districts.

The youth and loveliness of the bijin reflected the popular appreciation of transient pleasures in the Floating World, and these pictures played an important role in defining the visual culture of early modern Japan.

Introducción

El período Edo (1603–1868) marcó el inicio de una era de paz y prosperidad después de siglos de conflictos políticos y militares en Japón. Sin guerras por librar, los samurai (miembros de la clase guerrera dominante) se establecieron en las principales ciudades, como Tokio (llamada entonces, Edo), Kioto y Osaka, en las que patrocinaron artistas, comerciantes, animadores y cortesanos. Todos se mezclaron en lo que se conocía como el ukiyo, literalmente, “el Mundo Flotante,” una cultura urbana en la que florecieron las artes, el entretenimiento popular y los gastos extravagantes.

El período Edo (1603–1868) marcó el inicio de una era de paz y prosperidad después de siglos de conflictos políticos y militares en Japón. Sin guerras por librar, los samurai (miembros de la clase guerrera dominante) se establecieron en las principales ciudades, como Tokio (llamada entonces, Edo), Kioto y Osaka, en las que patrocinaron artistas, comerciantes, animadores y cortesanos. Todos se mezclaron en lo que se conocía como el ukiyo, literalmente, “el Mundo Flotante,” una cultura urbana en la que florecieron las artes, el entretenimiento popular y los gastos extravagantes.

Durante más de dos siglos y medio, se diseñaron ukiyo-e (imágenes del Mundo Flotante) sobre arte clásico, literatura y diseño popular para crear impresiones y pinturas de las actividades recreativas de la población urbana. Antes del siglo XVIII en Japón, mediante la impresión xilográfica (o impresión en sellos de madera) se reproducían principalmente textos escritos; las imágenes impresas eran generalmente en blanco y negro, o tenían que ser coloreadas a mano. La nueva tecnología que popularizó el maestro grabador Suzuki Harunobu en 1765 permitió la producción de impresiones policromas, para los que se utilizaba un bloque tallado por separado para cada color, a veces se usaban hasta veinte bloques por imagen. La temática de estas impresiones se amplió de manera gradual durante este período, desde cortesanos, actores Kabuki y otras características de la escena urbana hasta incluir imágenes vibrantes y expresivas de cuentos folklóricos, motivos budistas, modas, el mundo natural y acontecimientos históricos dramáticos.

Los más de 130 grabados y pinturas expuestos aquí, principalmente de la célebre Colección John Chandler Bancroft en el Museo de Arte de Worcester, abarcan la historia completa del género ukiyo-e, captando su diversidad en términos de tamaño, fecha, material, función, contenido y estilo. Estas extraordinarias obras testifican la habilidad artística y la visión de los diseñadores y grabadores/impresores de principios de la era moderna de Japón.

Los orígenes de Ukiyo

La palabra ukiyo se refería originalmente a la idea budista de la transitoriedad de la vida. El significado cambió durante el período Edo cuando el carácter que significaba “transitorio” fue reemplazado por un homónimo (palabra que se escribe o suena igual, pero que tiene un significado diferente) que significa “flotar”. La gente del pueblo cansada de la guerra, que bromeaba sobre encontrar descanso en el entretenimiento en vez de en la religión, celebró el hedonismo y la sensualidad del “Mundo Flotante”. La ética del Mundo Flotante está muy bien captada en la publicación de 1661 Ukiyo Monogatari (Cuentos del mundo flotante) de Asai Ryōi:

Vivir solo el momento, disfrutar de la luna, la nieve, las flores de cerezo y las hojas de arce, cantar canciones, beber sake y distraerse solo en el flotar, sin preocuparse por la posibilidad de la inminente pobreza, optimista y despreocupado, como una calabaza transportada por la corriente del río: a esto lo llamamos ukiyo.

La producción de xilografías

La mayoría de las obras de esta exposición se produjeron utilizando el proceso de mokuhanga, impresión xilográfica. En su forma más básica, esta técnica consistía en tallar y transferir un diseño en un bloque de madera, habitualmente hecho de madera de cerezo durable. El grabador aplicaba tinta en las líneas en relieve del diseño, colocaba una pieza de papel encima y utilizaba un objeto suave con forma de disco, denominado baren, para presionar la tinta sobre el papel. Para incorporar varios colores en la misma obra, el artista tallaba varios bloques de madera, cada uno imprimía los elementos individuales del diseño en un color específico.

Los bloques se podían reutilizar muchas veces y el grabador podía hacer ajustes pequeños en el diseño tallando para sacar o modificar partes de la imagen. En algunos casos, los bloques se volvían a imprimir muchos años después de su publicación inicial. La producción de impresiones por lo general requería la colaboración de un diseñador, un tallador, un impresor y un editor.

Si bien el tamaño y la forma de los grabados japoneses pueden variar muchísimo, las dimensiones del papel estaban reguladas en el período Edo. A continuación, se indican los tres tamaños de grabados estandarizados en exposición en estas galerías:

Oban (15 x 10 in) (38 x 25 cm): Este era el tamaño más común de los grabados ukiyo-e. Un diseño podía incorporar de dos a tres hojas (de manera horizontal o vertical), lo que permitía que el artista creara dípticos o trípticos.Hosoban (13 x 5.5 in) (33 x 14 cm): Este tamaño de grabado angosto y raro se utilizaba con frecuencia para los yakusha-e (grabados de actor) durante el siglo XVIII y kacho-e (grabados de pájaros y flores) durante el siglo XIX.Hashira-e (27 x 5 in) (69 x 13 cm): Este formato largo y estrecho, conocido también como "imágenes pilar”, se popularizó a comienzos del siglo XVIII y fue una alternativa generalizada a los rollos pintados más costosos, que se podían colgar en las alcobas de las casas.

Entretenimiento

Cuando Japón ingresó al período Edo, los daimyō (gobernantes feudales) luchaban por el poder. En la Batalla de Sekigahara en 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu derrotó a sus enemigos en una victoria decisiva y pronto estableció el Tokugawa Shogunate (gobierno militar), con él mismo a la cabeza. Sobrevino una era bastante pacífica y larga, lo que permitió que los residentes de las principales ciudades de Japón buscaran entretenimiento, en vez de guerras.

Como resultado, la mayoría de las ciudades de este período albergaron teatros, burdeles y distritos de compras prósperos, que recibían a clientes de todo tipo. El calendario público también estaba repleto de festivales, feriados y desfiles, lo que hizo que el jolgorio se convirtiera en un componente esencial de la vida urbana. Los lugares de entretenimiento disfrutaban del patrocinio de los miembros más adinerados de la sociedad, los daimyō y sus sirvientes samurai (quienes debían residir en Edo y rendir pleitesía al shogun cada dos años), como también los miembros de la clase media, muchos de los cuales eran comerciantes que habían prosperado al proveer bienes y servicios a los habitantes urbanos. Los diversos personajes y actividades de este ambiente vibrante se destacan entre los primeros temas por excelencia en ukiyo-e.

Imágenes poéticas

Floreció la producción y el consumo de la literatura en Japón durante el período Edo y esto reflejó en parte el alto índice de alfabetización entre los chōnin (la gente del pueblo). Componer poesía, dominar la caligrafía y escribir cartas eran actividades de la vida cotidiana para casi todos, independientemente de la clase social. Los textos clásicos, que antes solo estaban disponibles para los aristócratas, y los libros de literatura contemporánea se producían en cantidades enormes utilizando las nuevas técnicas de impresión xilográfica y tenían amplia circulación. Luego, los libros impresos se acompañaron de imágenes, y los temas se ampliaron para incluir guías de viaje, textos religiosos, comentarios políticos, tratados históricos artísticos, libros de autoayuda, ensayos, sátiras y ficción picaresca.

Ukiyo-e extrajo a partir de este canon literario vasto y creciente para ilustrar escenas que reflejaban las experiencias diarias de los que vivían en el Mundo Flotante. Las impresiones de hojas solas y los libros ilustrados contaban con un público capaz de interpretar señales visuales sobre los temas y narrativas. Desde el punto de vista del estilo, estas imágenes reflejaban la población del ukiyo de muchas maneras, fusionando el lenguaje visual aristocrático con las tradiciones de diseño relacionadas con las clases más bajas y la gente del pueblo.

El paisaje y el mundo natural

Las imágenes de pájaros, flores y otros elementos del mundo natural han sido integral durante mucho tiempo el arte de Japón, posiblemente en respuesta a la variedad y belleza del paisaje de la nación insular. Las prácticas indígenas sintoístas, que se basaban en creencias animistas en espíritus naturales, y también las ideas budistas sobre la transitoriedad y la vinculación de todos los seres vivos contribuyen a este deleite en las imágenes de la naturaleza. En la cultura más urbana que se desarrolló durante el período Edo, la variabilidad inherente de la naturaleza encontraba eco en la ética del Mundo Flotante, que se centraba en los placeres efímeros de la vida. Los artistas ukiyo-e buscaban captar la belleza momentánea de sus temas y solían centrarse en el paso de las estaciones, las flores y miradas fugaces de animales. Las imágenes que muestran el paisaje que rodea a la ciudad capital de Edo y los sitios famosos a lo largo de las rutas principales de Japón también fueron sumamente populares.

Bijin-ga: Imágenes de las bellezas de moda

Bijin habitualmente hace referencia a las bellas jóvenes de las imágenes del Mundo Flotante. En general, estas imágenes mostraban mujeres vestidas a la moda, muchas veces, cortesanas, sus rostros y figuras personificando el ideal de belleza de esa época. Esas imágenes tan glamorosas encubrían la cruda realidad de la vida diaria de las cortesanas en las zonas de prostíbulos.

La juventud y belleza de las bijin reflejaban la apreciación popular de los placeres efímeros en el Mundo Flotante, y estas imágenes desempeñaban un papel importante en la definición de la cultura visual de principios de la era moderna de Japón.