Anni Albers: In Thread and On Paper

Sunday, February 11, 2024 - Sunday, June 30, 2024

Anni Albers (1899–1994) is considered the most important textile artist of the 20th century. Known for her wall hangings, weavings, and designs, she was also an innovative educator and printmaker.

"Anni Albers: In Thread and On Paper" highlights how nimbly Albers moved between mediums—including her shift from weaving to printmaking in the 1960s—and transitioned between making art and designing functional and commercial objects. Drawn from the collection of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, the exhibition focuses on groundbreaking work from the last 40 years of her life. In addition to Albers’s woven rugs, tapestries, drawings, and prints, the exhibition features her loom and wallpaper based on her designs.

In weaving, designing, and printmaking, Albers’s faith in the power of abstraction never wavered. She understood material not only as a vehicle to carry ideas, but more importantly for its physical and structural potential. As she put it, “If we want to get from materials the sense of directness, the adventure of being close to the stuff the world is made of, we have to go back to the material itself, to its original state, and from there on partake in its stages of change.”

This exhibition is curated by Fritz Horstman, education director at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. The Blanton presentation is organized by Claire Howard, Associate Curator, Collections and Exhibitions.

"Anni Albers: In Thread and On Paper" is organized by The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

Gallery Text"Anni Albers: In Thread and On Paper" highlights how nimbly Albers moved between mediums—including her shift from weaving to printmaking in the 1960s—and transitioned between making art and designing functional and commercial objects. Drawn from the collection of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, the exhibition focuses on groundbreaking work from the last 40 years of her life. In addition to Albers’s woven rugs, tapestries, drawings, and prints, the exhibition features her loom and wallpaper based on her designs.

In weaving, designing, and printmaking, Albers’s faith in the power of abstraction never wavered. She understood material not only as a vehicle to carry ideas, but more importantly for its physical and structural potential. As she put it, “If we want to get from materials the sense of directness, the adventure of being close to the stuff the world is made of, we have to go back to the material itself, to its original state, and from there on partake in its stages of change.”

This exhibition is curated by Fritz Horstman, education director at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. The Blanton presentation is organized by Claire Howard, Associate Curator, Collections and Exhibitions.

"Anni Albers: In Thread and On Paper" is organized by The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

Introduction

Anni Albers: In Thread and On Paper comprises more than one hundred objects from the collection of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and others, covering the artist and designer’s wide-ranging career of seven decades. The exhibition highlights the nimbleness with which Albers moved between mediums and techniques as she produced works of art and designed more functional and commercial objects. Albers’s drawings, prints, textile samples, rugs, and writings demonstrate an expansive curiosity and multi-faceted artistic proficiency. The textile samples, many of which she wove on the loom on display, exemplify the strict vertical and horizontal matrix of weaving that Albers worked both with and against throughout her career and across mediums.

Foregrounding the transition from weaver to printmaker that Albers made during the 1960s, the exhibition begins with Connections, a series of nine silkscreen prints from 1983 in which Albers recreated designs from every decade of her long career. It then presents in greater detail the visual and material connections that drove her evolving studio practice.

Whether working in weaving, design, or printmaking, Albers’s faith in the power of abstraction never wavered. Throughout her widely varied, yet consistent and focused work, we see an artist who understood material not only as a vehicle for ideas, but also for its physical and structural potential. As she put it, “If we want to get from materials the sense of directness, the adventure of being close to the stuff the world is made of, we have to go back to the material itself, to its original state, and from there on partake in its stages of change.”

Biography

Anni Albers

1899–1994

Anni Albers was born Annelise Fleischmann in Berlin in 1899. Her early desire to be an artist led her in 1922 to the Bauhaus, the famous German school of art, architecture, and design. The Bauhaus was among the first art schools in Germany to accept both men and women, although most women, including Anni, were placed in the weaving workshop. It was there that her genius with threads first revealed itself in her designs for textiles and rugs. In 1931, she became head of the weaving department. At the Bauhaus she met fellow student Josef Albers, whom she married in 1925.

Anni and Josef Albers fled Germany for America when the Bauhaus closed in 1933 under pressure from the Nazis. They accepted teaching positions at the newly established Black Mountain College, a small, progressive, liberal arts school outside Asheville, North Carolina. At Black Mountain, Anni also began to focus on what she called her “pictorial weavings,” hand-woven pieces intended as artworks to be hung on the wall, not as fabrics for practical use.

The couple taught at Black Mountain College until 1949. That year, Anni became one of the first female artists to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which was also that museum’s first solo exhibition dedicated to the work of a textile artist. The Alberses moved to New Haven, Connecticut, in 1950 when Josef was appointed chairman of the Department of Design at Yale University. Anni made her first prints in 1963, and by 1969 she had transitioned entirely from weaving to printmaking. She and Josef lived in New Haven until 1970, and then in nearby Orange until Josef’s death in 1976 and Anni’s in 1994.

Anni Albers’s eight-harness Structo Artcraft 750 loom was produced by Structo Manufacturing Company in Freeport, Illinois. She had purchased two of them shortly after arriving in Connecticut in 1950. It is likely that she made the textile samples on display here on these looms.

Textile Samples

Like most weavers and textile designers, Albers found that the creation of samples was essential to her working practice. Samples allow a weaver to experiment with the effects of combining fibers of different colors or textures, or consider the transformative results of subtly changing a weaving structure.

From her earliest days at the Bauhaus until the end of her long career, Albers’s ideas first found form on graph paper. As she worked through hundreds of possibilities, only a few of which are displayed here, Albers experimented with patterns of triangles and related forms that seem both regular and wildly chaotic in their arrangements. She often enlarged these initial sketches on graph paper, transferring them to prints or applying them to textiles.

The looping, braided lines Albers used in a series of designs for rugs in 1959 reflect her expanding sense of design beyond the strict parameters of the loom. Here, she continues her investigation of the possibilities of thread breaking with this grid. During Albers’s lifetime, Design for a Rug was executed only in the form of a series of drawings and gouache paintings. It was not until a 2009 collaboration between the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and Christopher Farr Rugs that the entangled braided lines of the 1959 drawing, so closely suggesting the texture of tufting, were realized.

During the 1950s, Albers began working against the vertical and horizontal structure established by the weaving loom, experimenting with drawings that incorporated thread-like motifs in looping and non-rectilinear forms. After her first foray into printmaking in 1963 at Tamarind Lithography Studio in Los Angeles, she was invited to return in 1964. During that year, she made Line Involvements, a portfolio of seven lithographs depicting curls and knots of thread that appear to have been joyously released from the rigid confines of the loom.

Anni and Josef Albers first traveled to Mexico in the winter of 1935–36. Fascinated by the pre-Columbian art and architecture they saw there, they visited Mexico repeatedly over the next thirty years. In the ancient temples she visited on these trips, Anni became particularly focused on meander motifs, one of which appears in this photo of Albers with friends in Mitla. The continuous meandering angular line provided a design mechanism like that of weaving, but one that printmaking allowed her to explore more fully. Albers realized, for example, that a single silkscreen template could be turned and overlaid in ways that enrich the resulting image. She gave the following instructions for the printing of Red Meander:

Connections

Connections is a series of nine silkscreen prints made in 1983, in which Albers recreated images from every decade of her career as a weaver, designer, and printmaker. It embodies her ability to flow easily between mediums and techniques and demonstrates both the extraordinary range and consistency of her output over the years.

Loom

Anni Albers’s eight-harness Structo Artcraft 750 loom was produced by Structo Manufacturing Company in Freeport, Illinois. She had purchased two of them shortly after arriving in Connecticut in 1950. It is likely that she made the textile samples on display here on these looms.

Although the loom is quite small, its mechanism has harness-locking capabilities, which would have allowed Albers more flexibility and freedom to do time-consuming manual manipulation such as leno weaves, in which two or more warp threads are twisted together between rows of weft, creating openings in the structure of the weave.

Albers gave up weaving in 1968, and in 1970 she donated these looms to a local college. They were returned to the Albers Foundation in the late 1990s.

Textile Samples

Like most weavers and textile designers, Albers found that the creation of samples was essential to her working practice. Samples allow a weaver to experiment with the effects of combining fibers of different colors or textures, or consider the transformative results of subtly changing a weaving structure.

This selection of textile samples demonstrates the variety of textiles that Albers produced. It includes samples for industrial fabrics, gauze window coverings, and even one fabric designed for an evening coat.

Albers did not leave behind many designs for her weavings, so the textile samples provide crucial insight into her experiments with structure and material.

Designs on Graph Paper for Textiles and Prints

From her earliest days at the Bauhaus until the end of her long career, Albers’s ideas first found form on graph paper. As she worked through hundreds of possibilities, only a few of which are displayed here, Albers experimented with patterns of triangles and related forms that seem both regular and wildly chaotic in their arrangements. She often enlarged these initial sketches on graph paper, transferring them to prints or applying them to textiles.

Designs for a Rug

The looping, braided lines Albers used in a series of designs for rugs in 1959 reflect her expanding sense of design beyond the strict parameters of the loom. Here, she continues her investigation of the possibilities of thread breaking with this grid. During Albers’s lifetime, Design for a Rug was executed only in the form of a series of drawings and gouache paintings. It was not until a 2009 collaboration between the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and Christopher Farr Rugs that the entangled braided lines of the 1959 drawing, so closely suggesting the texture of tufting, were realized.

Line Involvements

During the 1950s, Albers began working against the vertical and horizontal structure established by the weaving loom, experimenting with drawings that incorporated thread-like motifs in looping and non-rectilinear forms. After her first foray into printmaking in 1963 at Tamarind Lithography Studio in Los Angeles, she was invited to return in 1964. During that year, she made Line Involvements, a portfolio of seven lithographs depicting curls and knots of thread that appear to have been joyously released from the rigid confines of the loom.

The master printers at Tamarind encouraged Albers to experiment with the workshop’s acid baths, creating mottled, cloudy grounds, then superimposed her linear designs over them.

Meander

Anni and Josef Albers first traveled to Mexico in the winter of 1935–36. Fascinated by the pre-Columbian art and architecture they saw there, they visited Mexico repeatedly over the next thirty years. In the ancient temples she visited on these trips, Anni became particularly focused on meander motifs, one of which appears in this photo of Albers with friends in Mitla. The continuous meandering angular line provided a design mechanism like that of weaving, but one that printmaking allowed her to explore more fully. Albers realized, for example, that a single silkscreen template could be turned and overlaid in ways that enrich the resulting image. She gave the following instructions for the printing of Red Meander:

1) 1 background screen, solid color.2) The cut design screen, 1/2” smaller than background screen. Print same color as background screen, placing it to upper left corner of background.3) Turn design screen upside down, placing it to lower right corner, print same color as background color.4) Use new design color diluted to be translucent (only few inks make this possible and retain sufficient coloring power). Turn screen back to first design position. Print it placing it equal distance from all edges.

Red Lines on Blue

Red Lines on Blue utilizes the same linear design seen in Albers’s 1976 print Triangulated Intaglio VI, seen nearby, and reproduced in the wallpaper hanging at the exhibition’s entrance. Albers introduced this maze-like pattern in her sketches on graph paper. It later appeared on a fabric that she designed in the early 1980s for the Sunar Textile Company, also on view here.

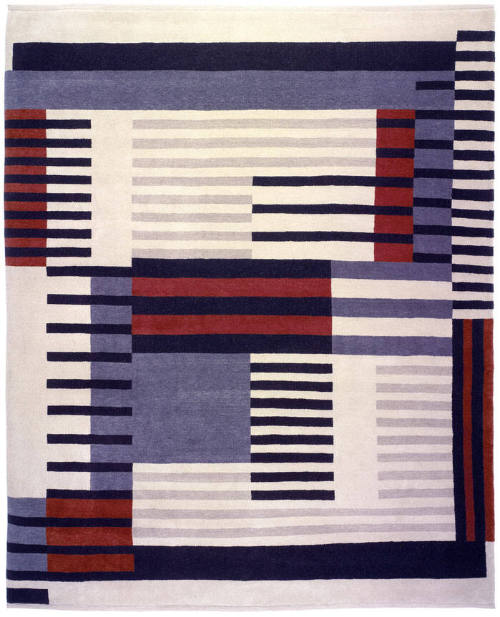

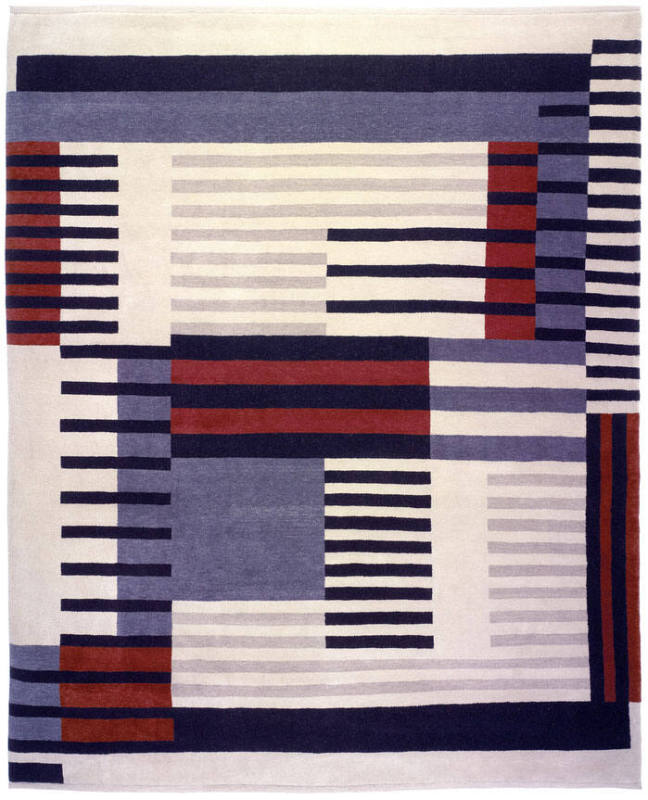

Smyrna-Knuepfteppich [Smyrna Knotted Rug]

This contemporary production of the Smyrna-Knuepfteppich [Smyrna Knotted Rug], executed by the company Christopher Farr Rugs in collaboration with the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, realizes Albers’s 1925 drawing for a rug, made when she was a student at the Bauhaus. It faithfully utilizes the type of knotting known as “Smyrna,” from which the design takes its name. The flat weave of the rug allows for particularly crisp lines and complicated patterns—qualities that Albers would embrace years later when she recreated this design in the print portfolio Connections, seen nearby.

Orchestra

The architect Phillip Johnson, whom Albers had known since his visit to the Bauhaus in 1927, designed AT&T's new headquarters at 550 Madison Avenue in Manhattan in 1983. He commissioned Albers to create four large tapestries, which she entitled Orchestra, to hang in the building’s Sky Lobby. These tapestries, two of which are displayed here, echo the Orchestra design she had first produced in 1979, also seen in the first room of this exhibition in Albers’s Connections portfolio of 1983.

Johnson had been instrumental in bringing Anni and Josef Albers to Black Mountain College in 1933, and organized Anni’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1949. The two also worked together on a 1950 guest house in midtown Manhattan for the Rockefeller family, for which Albers designed curtain fabric.

Sunar and S-Collection

In the late 1970s Albers was approached by the Sunar Textile Company, which later became S-Collection Textiles, to produce fabrics based on her designs. Albers’s designs capitalized on the industry’s new technologies and were produced using machined embroidery and acid etching on fabric. In Melfi, the machine-embroidered threads were cut in such a way that their ends create a tufted edge to the elements of the design.

Mountainous

Albers produced pencil sketches on graph paper for the series of experimental prints comprising Mountainous. At Tyler Graphics in Bedford, New York, the designs were transferred to deeply etched magnesium plates. Albers asked the master printers to skip the usual next step of inking the plates. Instead, they placed dampened paper on top of the un-inked plates, which were put through the printing press. The even pressure of the press embossed the high-relief pattern of the metal into the paper, producing elegant, completely white, embossed sheets that capture in subtle shadows the playful inventiveness of Albers’s design and her ability to coax unexpected results from the printing process.

Temple Emanu-El Ark Panel

In the mid-1950s, Albers was commissioned to design an ark covering for Temple Emanu-El in Dallas, Texas. Jewish by heritage, Albers designed eight panels, each 20 feet tall, that are still in place today. Traditionally a draped curtain, Albers’s innovative ark covering comprises panels of fabric mounted on tracks that slide open to reveal the synagogue’s Torah scrolls. Typical of her efficient thinking, each of the eight panels are identical, though their geometric patterns are offset or rotated to create a lively design in lustrous gold, silver, blue, and green. Albers’s preliminary study for the project appears here with a ninth spare panel that was discovered recently in the temple’s archives.

Introducción

Anni Albers: en hilo y sobre papel reúne más de un centenar de objetos de la colección de la Josef and Anni Albers Foundation y de otras instituciones. La muestra abarca las siete décadas de carrera de la artista y diseñadora. La exposición destaca la destreza con la que Albers se desplazaba entre diferentes medios y técnicas tanto para producir obras de arte como para diseñar objetos más funcionales y comerciales. Sus dibujos, grabados, muestras textiles, alfombras y escritos reflejan una curiosidad enorme y una habilidad artística polifacética. Las muestras textiles, muchas de las cuales tejió en el telar que se expone aquí, son un ejemplo del patrón de tejido estrictamente vertical y horizontal que Albers adoptó y rechazó a lo largo de su carrera y con los diferentes medios.

A fin de destacar la transición de tejedora a grabadora durante la década de 1960, la muestra comienza con Connections [Conexiones], una serie de nueve serigrafías de 1983 en las que Albers recreó diseños de cada una de las décadas de su larga trayectoria. A continuación se presentan con más detalle las conexiones visuales y materiales que impulsaron la evolución de su práctica de estudio.

Ya sea en el tejido, el diseño o el grabado, Albers nunca dudó del poder de la abstracción. En toda su obra, muy variada pero coherente y enfocada a la vez, observamos una artista para quien el material no era un mero vehículo para transmitir ideas; también tenía un potencial físico y estructural. En palabras de la artista: “Si queremos obtener de los materiales la sensación de naturalidad, la aventura de acercarse a eso de lo que está hecho el mundo, tenemos que volver al material en sí mismo, a su estado original, y a partir de allí, formar parte de sus etapas de cambio”.

Biografía

Anni Albers

1899–1994

Anni Albers nació como Annelise Fleischmann en Berlin en 1899. Deseaba ser artista desde muy joven, y en 1922 ingresó a la Bauhaus, la famosa escuela alemana de arte, arquitectura y diseño. La Bauhaus fue una de las primeras escuelas de arte de Alemania que aceptó tanto a hombres como a mujeres. Sin embargo, la mayoría de las mujeres, incluida Anni, debían matricularse en el taller de tejido. Es allí donde su destreza con los hilos pudo verse por primera vez en los diseños de tejidos y alfombras. En 1931, fue nombrada jefa del departamento de tejido. En la Bauhaus conoció a Josef Albers, otro estudiante, con quien se casó en 1925.

Cuando la Bauhaus cerró por presión del nazismo en 1933, Anni y Josef Albers huyeron de Alemania y llegaron a Estados Unidos. Se desempeñaron como docentes en el Black Mountain College, una escuela de arte pequeña, progresiva y liberal de las afueras de Asheville, en Carolina del Norte, que se había inaugurado hacía muy poco tiempo. En Black Mountain, Anni también comenzó a enfocarse en lo que llamó sus “tejidos pictóricos”, piezas tejidas a mano como obras de arte para colgar en la pared, no como tejidos para uso práctico.

La pareja dictó clases en Black Mountain College hasta 1949. Ese año, Anni se convirtió en la primera artista mujer en tener una exposición individual en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York, que fue también la primera exposición individual del museo dedicada a la obra de un artista textil. Anni y Josef Albers se mudaron a New Haven, Connecticut, en 1950, cuando Josef fue nombrado director del Departamento de Diseño de la Universidad de Yale. Anni hizo sus primeros grabados en 1963, y para 1969, se dedicaba por completo al grabado. Vivieron en New Haven hasta 1970, luego, cerca de Orange hasta el fallecimiento de Josef en 1976 y el de Anni, en 1994.

Conexiones

Connections [Conexiones] es una serie de nueve serigrafías que Albers hizo en 1983. En ellas recreó imágenes de cada una de las décadas de su extensa trayectoria como tejedora, diseñadora y grabadora. Es un testimonio de la habilidad de la artista para moverse con facilidad entre los diferentes medios y técnicas, y pone de manifiesto tanto la variedad como la coherencia extraordinaria de su obra a lo largo de los años.

Telar

El telar Structo Artcraft 750 de ocho arneses que perteneció a Anni Albers fue fabricado por el Structo Manufacturing Company en Freeport, Illinois. La artista adquirió dos telares de este modelo poco después de llegar a Connecticut en 1950. Es probable que los haya usado para tejer las muestras textiles que se exponen aquí.

Si bien el telar es bastante pequeño, tiene un mecanismo que permite trabar los arneses. Esto permitió a Albers más flexibilidad y libertad para hacer manipulaciones que le llevaban mucho tiempo, como los tejidos de gasa de vuelta, en los que dos o más hilos de urdimbre se entrelazan entre hileras de trama para crear aberturas en la estructura del tejido.

Albers dejó de tejer en 1968, y en 1970 donó estos telares a una universidad local. A fines de la década de 1990, fueron devueltos a la Albers Foundation.

Muestras textiles

Como la mayoría de los tejedores y diseñadores textiles, Albers consideraba que crear muestras era esencial en su práctica laboral. Las muestras le permiten al artista experimentar con los efectos de combinar fibras de distintos colores o texturas, o considerar los resultados transformadores de cambiar sutilmente una estructura del tejido.

Esta selección de muestras textiles pone de manifiesto la variedad de tejidos que produjo Albers. Incluye muestras de tejidos industriales, telas de gasa para cubiertas de ventana e incluso un tejido diseñado para un abrigo.

Albers no conservó muchos diseños de sus tejidos, por lo que las muestras textiles nos brindan una visión crucial de sus experimentos con la estructura y el material.

Diseños sobre papel cuadriculado para textiles y estampados

Desde sus inicios en la Bauhaus hasta el final de su extensa carrera, Albers primero plasmaba sus ideas en papel cuadriculado. Albers experimentó con cientos de posibilidades —de las que aquí solo se exponen unas pocas—, entre ellas, patrones de triángulos y formas relacionadas que parecen a la vez ordenadas y extremadamente caóticas en su disposición. A menudo ampliaba estos bocetos iniciales en papel cuadriculado y los transfería a grabados o los aplicaba a los tejidos.

Diseños para una alfombra

Las líneas entrelazadas y en bucle que Albers utilizó en una serie de diseños de alfombras en 1959 reflejan su amplio sentido del diseño más allá de los estrictos parámetros del telar. Aquí continúa explorando las posibilidades de los hilos rotos con esta cuadrícula. En vida, Albers solo pudo realizar Design for a Rug [Diseño para una alfombra] en una serie de dibujos y pinturas de guache. En 2009, gracias a una colaboración entre la Fundación Josef y Anni Albers y Christopher Farr Rugs, finalmente se materializaron las líneas trenzadas y enredadas del dibujo de 1959, que tanto sugieren la textura de un mechón.

Enredos lineales

Durante la década de 1950, Albers comenzó a rechazar la estructura vertical y horizontal establecida por el telar. Comenzó a experimentar con dibujos que incorporaban motivos con figuras de hilos en bucle y formas no rectilíneas. Luego de su primera exposición de grabados en 1963 en el Tamarind Lithography Studio de Los Ángeles, la invitaron nuevamente en 1964. Ese año realizó Line Involvements [Enredos lineales], un catálogo de siete litografías que representan rizos y nudos de hilo que parecen moverse alegremente, liberados de los rígidos confines del telar.

Los maestros impresores de Tamarind animaron a Albers a que experimentara en el taller con baño de ácido, que da como resultado un fondo moteado y opaco al que luego superponía sus diseños lineales.

Meandro

Anni y Josef Albers viajaron por primera vez a México en el invierno de 1935-36. Fascinados por el arte y la arquitectura precolombinos que vieron allí, regresaron varias veces durante los siguientes treinta años. En los templos antiguos que visitó en estos viajes, Anni quedó especialmente fascinada con los motivos de los meandros, uno de los cuales aparece en esta foto de Albers con amigos en Mitla. La línea angular continua y serpenteante le brindaba un mecanismo de diseño similar al del tejido, pero que con el grabado podía explorar más a fondo. Albers se dio cuenta, por ejemplo, de que una sola plantilla serigráfica podía girarse y superponerse de formas que enriquecían la imagen final. La artista dejó las siguientes instrucciones para la impresión de Red Meander [Meandro rojo]:

1) 1 pantalla de fondo, color sólido.2) Corte de la pantalla de diseño: 1,3 cm más pequeña que la pantalla de fondo. Imprimir del mismo color que la pantalla de fondo; colocarla en la esquina superior izquierda del fondo.3) Voltear la pantalla de diseño y colocarla en la esquina inferior derecha, imprimir del mismo color que el color del fondo.4) Utilizar un nuevo color de diseño diluido para que sea translúcido (solo algunas tintas pueden lograrlo y conservar suficiente poder de coloración). Volver a colocar la pantalla en la primera posición de diseño. Imprimir colocándola a la misma distancia de todos los bordes.

Líneas rojas sobre azul

Red Lines on Blue [Líneas rojas sobre azul] utiliza el mismo diseño lineal que el grabado de Albers de 1976 Triangulated Intaglio VI [Intaglio triangulado VI], expuesto en las inmediaciones, y que se reproduce en el papel pintado que cuelga en la entrada de la exposición. Albers introdujo este patrón laberíntico en sus bocetos sobre papel cuadriculado. Posteriormente, apareció en una tela que diseñó a principios de los años ochenta para la Sunar Textile Company, también expuesta aquí.

Smyrna-Knuepfteppich [Alfombra Esmirna]

Esta producción contemporánea de Smyrna-Knuepfteppich [Alfombra Esmirna], elaborada por la compañía Christopher Farr Rugs en colaboración con la Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, llevó a la realidad el dibujo de una alfombra que Albers realizó en 1925, cuando estudiaba en la Bauhaus. Emplea con fidelidad el tipo de anudado conocido como “Esmirna”, del que el diseño toma su nombre. El tejido plano de la alfombra da lugar a líneas especialmente nítidas y patrones complejos, cualidades que Albers adoptaría años más tarde cuando recreó este diseño en la carpeta de grabados Connections (Conexiones), expuesta en la sala.

Orquesta

El arquitecto Phillip Johnson, a quien Albers conoció en su visita a la Bauhaus en 1927, diseñó en 1983 la nueva sede de AT&T en 550 Madison Avenue, Manhattan. Encargó a Albers la creación de cuatro grandes tapices, que tituló Orquesta, para colgarlos en el Sky Lobby del edificio. Estos tapices, dos de los cuales se exponen aquí, remiten al diseño de Orquesta que había realizado en 1979, que también puede verse en la primera sala de esta exposición en el catálogo Conexiones de Albers de 1983.

Johnson, quien tuvo un papel fundamental en la llegada de Anni y Josef Albers en el Black Mountain College en 1933, organizó la exposición individual de Anni en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York en 1949. Además, Johnson y Anni trabajaron juntos en 1950 en una casa de huéspedes en el centro de Manhattan para la familia Rockefeller. Albers contribuyó con el diseñó de las telas para las cortinas.

Sunar y S-Collection

A finales de la década de 1970, la Sunar Textile Company, que más tarde se convertiría en S-Collection Textiles, se puso en contacto con Albers para producir telas basadas en sus diseños. Los diseños de Albers aprovechaban las nuevas tecnologías de la industria y se producían mediante bordado a máquina y grabado al ácido sobre tela. En Melfi, los hilos bordados a máquina se cortaron de tal forma que sus extremos crean un borde empenachado en los elementos del diseño.

Montañoso

Albers realizó bocetos a lápiz sobre papel cuadriculado para la serie de grabados experimentales Mountainous [Montañoso]. En Tyler Graphics, de Bedford, Nueva York, los diseños se transfirieron a placas de magnesio profundamente grabadas. Albers pidió a los maestros impresores que omitieran el paso habitual de entintar las planchas. En cambio, usaron papel húmedo sobre las planchas sin entintar y luego las colocaron en la prensa. La presión uniforme de la prensa estampaba en el papel el patrón en alto relieve del metal. Esto daba como resultado elegantes hojas en relieve completamente blancas, que, con sutiles sombras, captaban la divertida creatividad del diseño de Albers y su habilidad para obtener resultados inesperados del proceso de impresión.

Panel de la cubierta del arca hejal del templo Emanu-El

A mediados de la década de 1950, Albers recibió el encargo de diseñar los paneles de una cubierta del arcapara el templo Emanu-El de Dallas, Texas. De herencia judía, Albers diseñó ocho paneles de seis metros de altura cada uno, que aún se conservan. La innovadora cubierta del arca de Albers, que tradicionalmente es una cortina drapeada, consta de paneles de tela montados sobre rieles que se deslizan para mostrar los rollos de la Torá de la sinagoga. Propio del pensamiento eficiente de la artista, cada uno de los ocho paneles es idéntico, aunque sus patrones geométricos se desplazan o giran para crear un diseño dinámico en reluciente oro, plata, azul y verde. Aquí se expone el estudio preliminar de Albers para el proyecto, que tiene un noveno panel sobrante que se descubrió en los archivos del templo hace poco.