Day Jobs

Sunday, February 19, 2023 - Sunday, July 23, 2023

One of the typical measures of success for artists is the ability to quit their day jobs and focus full time on making art. Yet these roles are not always an impediment to an artist’s career. This exhibition illuminates how day jobs can spur creative growth by providing artists with unexpected new materials and methods, working knowledge of a specific industry that becomes an area of artistic interest or critique, or a predictable structure that opens space for unpredictable ideas. As artist and lawyer Ragen Moss states:

Typologies of thought are more interrelated than bulky categories like ‘lawyer’ or ‘artist’ allow. . . Creativity is not displaced by other manners of thinking; but rather, creativity runs alongside, with, into, and sometimes from other manners of thinking.

Day Jobs, the first major exhibition to examine the overlooked impact of day jobs on the visual arts, is dedicated to demystifying artistic production and upending the stubborn myth of the artist sequestered in their studio, waiting for inspiration to strike. The exhibition will make clear that much of what has determined the course of modern and contemporary art history are unexpected moments spurred by pragmatic choices rather than dramatic epiphanies. Conceived as a corrective to the field of art history, the exhibition also encourages us to more openly acknowledge the precarious and generative ways that economic and creative pursuits are intertwined.

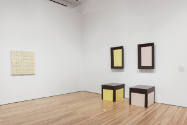

The exhibition will feature work produced in the United States after World War II by artists who have been employed in a host of part- and full-time roles: dishwasher, furniture maker, graphic designer, hairstylist, ICU nurse, lawyer, and nanny–and in several cases, as employees of large companies such as Ford Motors, H-E-B Grocery, and IKEA. The exhibition will include approximately 75 works in a broad range of media by emerging and established artists such as Emma Amos, Genesis Belanger, Larry Bell, Mark Bradford, Lenka Clayton, Jeffrey Gibson, Jay Lynn Gomez, Tishan Hsu, VLM (Virginia Lee Montgomery), Ragen Moss, Howardena Pindell, Chuck Ramirez, Robert Ryman, and Fred Wilson, among many others.

Day Jobs is organized by the Blanton Museum of Art.

Presenting Partner: Indeed

Generous funding for this exhibition is provided in part by the National Endowment for the Arts, John H. Baker and Christine Ogata, Ellen and David Berman, and Anthony and Celeste Meier; with additional support from Suzanne Deal Booth, Nicole and George Jeffords, Jeanne and Michael Klein, the Robert Lehman Foundation, and Kathleen Irvin Loughlin and Christopher Loughlin. Support is also provided by Leah Bennett, Carol LeWitt, and Lea Weingarten.

Gallery TextTypologies of thought are more interrelated than bulky categories like ‘lawyer’ or ‘artist’ allow. . . Creativity is not displaced by other manners of thinking; but rather, creativity runs alongside, with, into, and sometimes from other manners of thinking.

Day Jobs, the first major exhibition to examine the overlooked impact of day jobs on the visual arts, is dedicated to demystifying artistic production and upending the stubborn myth of the artist sequestered in their studio, waiting for inspiration to strike. The exhibition will make clear that much of what has determined the course of modern and contemporary art history are unexpected moments spurred by pragmatic choices rather than dramatic epiphanies. Conceived as a corrective to the field of art history, the exhibition also encourages us to more openly acknowledge the precarious and generative ways that economic and creative pursuits are intertwined.

The exhibition will feature work produced in the United States after World War II by artists who have been employed in a host of part- and full-time roles: dishwasher, furniture maker, graphic designer, hairstylist, ICU nurse, lawyer, and nanny–and in several cases, as employees of large companies such as Ford Motors, H-E-B Grocery, and IKEA. The exhibition will include approximately 75 works in a broad range of media by emerging and established artists such as Emma Amos, Genesis Belanger, Larry Bell, Mark Bradford, Lenka Clayton, Jeffrey Gibson, Jay Lynn Gomez, Tishan Hsu, VLM (Virginia Lee Montgomery), Ragen Moss, Howardena Pindell, Chuck Ramirez, Robert Ryman, and Fred Wilson, among many others.

Day Jobs is organized by the Blanton Museum of Art.

Presenting Partner: Indeed

Generous funding for this exhibition is provided in part by the National Endowment for the Arts, John H. Baker and Christine Ogata, Ellen and David Berman, and Anthony and Celeste Meier; with additional support from Suzanne Deal Booth, Nicole and George Jeffords, Jeanne and Michael Klein, the Robert Lehman Foundation, and Kathleen Irvin Loughlin and Christopher Loughlin. Support is also provided by Leah Bennett, Carol LeWitt, and Lea Weingarten.

Introduction

This exhibition was inspired by stories shared by artists about day jobs that indelibly shaped their practices. Often we learn about an artist’s formal training or other artists they admire, but not about how their work as a hairstylist, janitor, nanny, hardware developer, or lawyer has been instrumental to their art-making. This exhibition explores what happens when we foreground this background and take these overlooked lived experiences into account.

Day Jobs features work produced in the United States by approximately forty emerging and established artists. The exhibition is organized loosely into sections that reflect the diverse industries represented by the artists: Art World; Service Industry; Industrial Design; Media and Advertising; Fashion and Design; Caregivers; and Finance, Tech, and Law.

In the United States, specific conditions of labor and modest government support contribute to the prevalence of artists taking on day jobs. Success for an artist is often measured by their ability to quit a day job and focus full-time on creating art. Yet day jobs aren’t always obstacles to artists’ careers. Employment can spur creative growth by providing artists with unexpected materials and methods, hands-on knowledge of a specific industry that becomes an area of artistic investigation, or a predictable paycheck and structure that enable unpredictable ideas. The exhibition seeks to demystify artistic production and overturn the romanticized concept of the artist sequestered in their studio, waiting for inspiration to strike. As a corrective to traditional art-historical narratives, Day Jobs encourages us to acknowledge the precarious and generative ways that economic and creative pursuits are intertwined.

Art World

There would be no art world without artists. Museums, galleries, and the related businesses that support them rely on artists not only to produce work for display, but also to fill crucial behind-the-scenes roles necessary for the art world to function, ranging from museum educators to crate builders, shippers, and framers, to name a few. The impact on artists of such day jobs can be unexpectedly profound.

Fred Wilson’s work as a museum educator, for example, is crucial to understanding his art and the institutional critique he pioneered: artistic interventions into museum collections that help expose their hierarchies and omissions. “Working in the education department at the Met and at the Museum of Natural History, I was very aware of what wasn’t being shown to the public,” he recalls. “Those were the experiences that really got me thinking.” Wilson’s day job gave him an inside perspective on an industry that enabled him to expose and deconstruct it.

Service Industry

It is hard to imagine the service industry without artists, musicians, actors, and writers. As the largest and broadest sector in this exhibition, it includes artists who have worked as wait staff, dishwasher, house painter, janitor, and a host of other similar roles. Direct connections to these forms of employment are evident. Frank Stella’s Miniature Benjamin Moore Series paintings acknowledge his background as a house painter in their very title. Other works by artists address the nature and challenges of these occupations through their subject matter.

Media and Advertising

One of the most expected ways American artists have supported themselves is by working as commercial illustrators, graphic designers, billboard painters, and in other capacities connected to media and advertising. Although the influence of day jobs on artists’ practices is distinct for each artist, working in media and advertising is a direct link. Individuals adapt strategies from these trades to critique industry’s appeals to consumption: to dismantle a language, you have to first master it.

James Rosenquist credits his training as a billboard painter for giving him the techniques he transferred to his enigmatic paintings—in particular, his ability to work effectively on a monumental scale and a fascination with extreme close-ups that become abstractions. Barbara Kruger spent nearly a decade as an award-winning graphic designer for Condé Nast in New York, acknowledging: “my work as a graphic designer, with a few adjustments, became my art.” While New York has historically been the center for the media and advertising industry, this exhibition also includes the late San Antonio–based artist Chuck Ramirez, who designed and photographed brand packaging in the 1990s for the iconic Texas grocery chain H-E-B.

The design and fashion industries have natural affinities with the visual arts, so it is not surprising that artists would frequently seek employment in these arenas. What is interesting and noteworthy is the way artists in these sectors often deliberately blur the lines between commerce and art. Richard Artschwager’s sculptures bear uncanny resemblances to functional furniture. And Jeffrey Gibson has expressed his love of a good window display; he thinks about the presentation of his art in ways that unapologetically borrow from retail stores.

Jay Lynn Gomez’s artistic commitment to bringing visibility to Latino and Mexican housekeepers, gardeners, and pool cleaners came from her experience as a live-in nanny in Beverly Hills: “I would look at magazines like Architectural Digest on my break. The magazines looked like the very environments I was working in, minus all the people I was working with. It was an erasure of us. So it became very clear what to add. It was inspired by saying, ‘I’m here. We exist.’”

Tishan Hsu and Jim Campbell’s jobs at a corporate law firm and Silicon Valley tech company, respectively, helped them consider paths where their technological and nascent artistic interests might converge. Hsu’s time as a word processor for a Wall Street law firm in the 1980s led him to produce prescient paintings that consider the ways technology has fundamentally altered our lives and bodies: “I didn’t realize at the time was how the disembodied experience of my job, sitting in front of a screen, would become a paradigm for my art practice.”

In her video practice, VLM similarly choreographs symbols and sounds. Recurrent motifs in her short, dreamlike videos include visual images such as dripping honey, butterflies, moths, disembodied long, blond ponytails, and ASMR-like soundtracks of her recordings of Texas thunderstorms, wind chimes, and dripping water. In contrast to the shorthand legibility of the illustrations VLM uses as a graphic facilitator, her videos invoke multifaceted associations. She describes being drawn to butterflies, for example, because of their historical association with rebirth, but also because of their connection to the “butterfly effect”—the theory that small gestures in the natural world can generate big changes. Whether magnifying the eyespots of a butterfly, the eye of a storm, or a gooey cheese danish, her lexicon of circles and holes offers portals into other ways of being and seeing, potential sites of transformation and healing.

Design and Fashion

Standard biographies for artists online or provided by a commercial gallery typically share the schools that an artist attended and noteworthy exhibitions that have featured their work. Rarely do we learn, however, about how artists have supported themselves financially: that Emma Amos, for example, honed her skills as a weaver by working for one of the country’s largest commercial carpet companies. Or that Jeffrey Gibson assembled merchandise displays for IKEA’s Bayonne, New Jersey store early in his career. Or, according to Genesis Belanger, that working as an assistant to a prop stylist offered her “a backstage pass” to how “the most powerful images in our culture are made”—something she channels into her stoneware sculptures in smart and seductive ways.

Caregivers

From nurses to nannies, caregivers perform some of the most crucial jobs in the world. This concept of care manifests itself through the content, materials, and processes that artist caregivers employ in their artistic practices. The fact that many of these occupations have been, and still are, dominated by women and people of color also registers in meaningful ways.

Lenka Clayton’s Artist Residency in Motherhood is a cornerstone of this exhibition. In 2012, instead of considering the recent birth of her first child a potential detriment to her artistic practice, Clayton decided to make art from her experiences as a parent and created a residency out of her Pittsburgh home: “It became important to me to visibly occupy both roles of parent and artist, in order to contradict this story that asks women (and very rarely men) to make a choice between them.” The self-imposed limitations of her residency proved enormously productive and, at the request of other artists, Clayton created a website so that other artist mothers could adapt the framework for themselves. Today there are over 900 residents in 62 countries from Iran to Bangladesh.

Finance, Tech, and Law

Finance, tech, and law might seem like areas that would less frequently intersect with art-making. For many artists, the repetitive nature of tasks performed at day jobs can paradoxically stimulate new ways of thinking. Artistic discoveries are as likely to emerge amidst daily routines as they are from emotional dramas.

For Ragen Moss, for example, the seemingly disparate fields of art and law offer a kind of productive cross-training. As she states, “having a very different kind of work (such as practicing law), rather than drain energy away from making art…seems to serve as a counterintuitive lever to crest-up waves of creative ideas.” Her sculptures also reveal a tangible connection to her work as a practicing attorney as they often feature text from legal documents.

VLM (Virginia L. Montgomery)

The works by VLM (Virginia L. Montgomery) featured inside the Film and Video Gallery are part of the major exhibition Day Jobs, opening in the Butler Gallery downstairs in February 2023. VLM describes herself as an artist who “thinks in symbols.” For over a decade, she has worked as a graphic facilitator, mapping concepts in diverse settings ranging from health care conferences to the launch of an app at South by Southwest in Austin. Graphic facilitation—a niche field developed in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1970s—involves distilling ideas into words and pictures on giant white boards so that participants can better absorb the content being shared.

Introducción

Está exposición se inspiró en las historias compartidas por los artistas respecto de los trabajos diurnos que marcaron sus prácticas de forma permanente. Muchas veces nos enteramos de la educación formal de un artista o de otros artistas a los que admira, pero no de cómo su trabajo en áreas como la peluquería, la conserjería, el cuidado de personas, el desarrollo de hardware o el derecho ha sido fundamental para sus creaciones artísticas. Esta exposición explora lo que sucede cuando ponemos énfasis en estos antecedentes y tenemos en cuenta las experiencias vividas que se pasaron por alto.

Day Jobs (Trabajos diurnos) presenta las obras realizadas en Estados Unidos por alrededor de cuarenta artistas principiantes y reconocidos. En líneas generales, la exposición se organiza en secciones que reflejan los diversos sectores representados por los artistas: El mundo del arte; La industria de los servicios; Diseño industrial; Medios y publicidad; Moda y diseño; Personal de cuidado, y Finanzas, tecnología y derecho.

En Estados Unidos, las condiciones laborales específicas y la modesta ayuda del Estado contribuyen a que prevalezcan los artistas que toman trabajos diurnos. El éxito para un artista suele medirse en función de su capacidad para renunciar a su trabajo diurno y centrarse por completo en la creación de su arte. Sin embargo, los trabajos diurnos no siempre representan un obstáculo para la carrera artística. El empleo puede impulsar el crecimiento creativo, ya que brinda a los artistas materiales y métodos inesperados, conocimiento de primera mano sobre un sector específico que se convierte en un área de investigación artística, o bien un salario y una estructura predecibles que posibilitan el surgimiento de ideas impredecibles. La exposición busca desmitificar la producción artística y terminar con el concepto idealizado del artista recluido en su estudio, a la espera de un golpe de inspiración. Como corrección a las narrativas tradicionales de la historia del arte, Day Jobs (Trabajos diurnos) nos anima a reconocer las formas precarias y generadoras de entrelazarse que tienen las actividades económicas y creativas.

El mundo del arte

El mundo del arte

El mundo del arte no existiría sin artistas. Los museos, las galerías y las empresas relacionadas que apoyan estos espacios dependen de los artistas no solo para que produzcan el arte que se exhibirá, sino también para que ocupen puestos cruciales "detrás de escena" que son necesarios para que el mundo del arte funcione. Así, los artistas trabajan en áreas como, por ejemplo, la educación en los museos, la construcción de cajas, el transporte y la enmarcación. El impacto en los artistas de esos trabajos diurnos puede ser sorprendentemente profundo.

El trabajo de Fred Wilson como docente en museos, por ejemplo, es fundamental para entender su arte y la crítica institucional de la que fue pionero: intervenciones artísticas en las colecciones de los museos que permiten exponer sus jerarquías y sus omisiones. "Trabajar en el departamento de formación del Met y del Museum of Natural History sirvió para que me diera cuenta de lo que no se le estaba mostrando al público", recuerda Wilson. "Esas fueron las experiencias que me hicieron pensar de verdad". El trabajo diurno de Wilson le dio una perspectiva interna del sector, perspectiva que le permitió exponer esta industria y deconstruirla.

Larry Bell, conocido por sus esculturas de cubos de vidrio, empezó su carrera como pintor. Mientras trabajaba para sostenerse económicamente en una tienda de marcos en el valle de San Fernando durante la década de 1960, Bell descubrió, en una placa de vidrio agrietada, cualidades especiales de este material: "reflejaba la luz", explica Bell, "transmitía luz y también la absorbía, todo al mismo tiempo". A partir de allí, su vida cambió de rumbo. Muchas de las obras de esta exposición dan cuenta de que las revelaciones creativas pueden surgir de experiencias inesperadas, a menudo casuales, en los trabajos diurnos.

Los trabajadores inmigrantes constituyen una parte esencial de la vida y la fuerza laboral estadounidense. La siguiente sala expone tributos a los trabajadores inmigrantes realizados por la artista venezolana Violette Bule, establecida en Houston. Se presenta, especialmente, el homenaje a Johnny, su compañero de trabajo en una panadería del Lower East Side de Manhattan que sacaba la basura y ordenaba y pulía la vajilla en el sótano por cinco dólares la hora. La impactante escultura de Bule evoca la vulnerabilidad de sus circunstancias, a la vez que rinde homenaje a su dedicación y perseverancia.

James Rosenquist reconoce su formación como pintor de carteles, ya que esta actividad le permitió adquirir las técnicas que luego transfirió a sus enigmáticas pinturas, en particular, su habilidad para trabajar con eficacia a escalas monumentales y su fascinación por los primeros planos extremos que se convierten en abstracciones. Barbara Kruger pasó casi una década trabajando como diseñadora gráfica premiada para Condé Nast en Nueva York, y reconoce: "mi trabajo como diseñadora gráfica, con algunos ajustes, se transformó en mi arte". Si bien Nueva York ha sido, históricamente, el centro para la industria de los medios y la publicidad, esta exposición también incluye al fallecido artista de San Antonio, Chuck Ramirez, quien diseñó y fotografió la presentación de la marca para la icónica cadena de supermercados de Texas H-E-B durante la década de 1990.

Las industrias de la moda y el diseño tienen afinidades naturales con las artes visuales, por lo cual no sorprende que los artistas se inclinen por buscar trabajos en estos sectores. Lo que resulta interesante y digno de destacar es cómo los artistas de estos sectores suelen desdibujar deliberadamente las líneas entre el comercio y el arte. Las esculturas de Richard Artschwager tienen un asombroso parecido con los muebles funcionales. Y Jeffrey Gibson ha expresado su pasión por las buenas vidrieras: cuando analiza la presentación de su arte, toma detalles de las tiendas minoristas, sin reparo alguno.

El compromiso artístico de Jay Lynn Gomez de darle visibilidad al personal doméstico, los jardineros y los limpiadores de piletas de origen latino y mexicano provino de su experiencia como niñera en Beverly Hills: "Solía mirar revistas como Architectural Digest durante mis recreos. Esas revistas mostraban entornos muy parecidos a aquel en el que trabajaba, sin todas las personas con las que yo trabajaba. Nos borraban de esos espacios. Por lo que me resultó muy claro qué era necesario agregar. Me inspiré en el pensamiento 'Aquí estoy: Nosotras existimos'".

Los trabajos de Tishan Hsu y Jim Campbell en una oficina de abogados y en una empresa de tecnología, respectivamente, les permitieron considerar caminos en los que pudieran hacer converger sus intereses tecnológicos y sus inquietudes artísticas emergentes. El tiempo que Hsu trabajó como procesador de textos para una oficina de abogados de Wall Street en la década de 1980 lo llevaron a crear pinturas proféticas que analizan las maneras en que la tecnología ha alterado la esencia de nuestras vidas y nuestros cuerpos: "De lo que no me di cuenta en su momento es de cómo la experiencia incorpórea de mi trabajo, de estar sentado frente a una pantalla, se convertiría en un paradigma para mi práctica artística".

En su práctica de video, VLM también compone coreografías de símbolos y sonidos. Los motivos recurrentes de sus videos cortos y surrealistas incluyen imágenes como, por ejemplo, miel que chorrea, mariposas, polillas, colas de caballo largas, rubias e incorpóreas y bandas sonoras ambientales y calmas similares a las de Respuesta Sensorial Meridiana Autónoma (ASMR, en inglés) que crea a partir de sus grabaciones de tormentas en Texas, campanillas de viento y agua que gotea. En contraste con la legibilidad taquigráfica de las ilustraciones que VLM utiliza como representadora gráfica, sus videos evocan asociaciones multifacéticas. Explica que se siente atraída por las mariposas, por ejemplo, debido a su histórica asociación con la idea de renacer, pero, además, por su conexión con el “efecto mariposa” —la teoría de que pequeños gestos en el mundo natural pueden generar grandes cambios—. Ya sea que lo haga mediante la magnificación de los ojos de una mariposa, el ojo de una tormenta o un trozo de queso pegajoso de un pan danés, su léxico de círculos y orificios ofrece portales hacia otras formas de ser y observar, espacios potenciales de transformación y sanación.

La industria de los servicios

Es difícil imaginar la industria de los servicios sin los artistas, los músicos, los actores y los escritores. Este sector es el más grande y amplio de la exposición, e incluye artistas que trabajaron como camareros, lavaplatos, pintores de casas, conserjes y un sinfín de trabajos similares. Las relaciones directas con esos tipos de empleos son evidentes. Las obras de Frank Stella, Miniature Benjamin Moore Series (serie Miniatura de Benjamin Moore), da cuenta de su pasado como pintor de casas ya desde el título mismo. Otras obras abordan la naturaleza y los desafíos de estas ocupaciones a través de su temática.

Medios y publicidad

Una de las formas más obvias en que los artistas estadounidenses han podido sostenerse económicamente es trabajando como ilustradores comerciales, diseñadores gráficos, pintores de carteles y otros trabajos relacionados con los medios y la publicidad. Si bien el impacto de los trabajos diurnos en las prácticas de los artistas es distinta para cada uno de ellos, con el trabajo en los medios y la publicidad el vínculo es directo. Quienes trabajan en estas áreas adaptan las estrategias de estos oficios a fin de criticar las apelaciones al consumo que hace el sector: para desmantelar un lenguaje, primero hay que dominarlo.

Diseño y moda

Las biografías tradicionales de los artistas que se pueden leer en línea o que ofrecen las galerías comerciales, por lo general, brindan información sobre las escuelas a las que asistió el artista y las exposiciones más importantes que mostraron sus obras. Pero no solemos obtener información sobre cómo hizo el artista para poder sostenerse económicamente. Por ejemplo, no cuentan que Emma Amos perfeccionó sus habilidades como tejedora trabajando para una de las empresas comerciales de alfombras más grandes del país. Ni mencionan que, a principios de su carrera, Jeffrey Gibson se encargaba de acomodar la mercadería en exhibición para la tienda de IKEA de la ciudad de Bayonne en Nueva Jersey. Así como tampoco hacen referencia a que, según Genesis Belanger, trabajar como asistente de un estilista de utilería le permitió obtener "un pase detrás de escena" para saber cómo "se conciben las imágenes más poderosas de nuestra cultura", aspecto que se ve reflejado en sus esculturas de gres de forma ingeniosa y seductora.

Personal de cuidado

Desde las enfermeras hasta las niñeras, el personal de cuidado hace uno de los trabajos más importantes del mundo. Este concepto del cuidado se manifiesta a través del contenido, los materiales y los procesos que los artistas de cuidado utilizan en sus prácticas artísticas. El hecho de que la mayoría de estos puestos hayan sido, y aún lo sean, ocupados por mujeres y personas de color también se registra de maneras significativas.

La obra Artist Residency in Motherhood (Residencia de una artista en la maternidad) de Lenka Clayton es una pieza clave de esta exposición. En 2012, en lugar de pensar el reciente nacimiento de su primer hijo como un potencial detrimento para su práctica artística, Clayton decidió hacer arte con sus experiencias como madre y crear una residencia a partir de su hogar en Pittsburgh: "Se volvió importante para mí poder desempeñar de forma visible ambos roles, el de madre y el de artista, a fin de contradecir este relato de que las mujeres (muy rara vez los hombres) deben elegir uno de ellos". Las limitaciones autoimpuestas de su residencia resultaron ser enormemente productivas y, a pedido de otros artistas, Clayton creó un sitio web para que otras madres artistas pudieran adaptar el marco conceptual para ellas mismas. En la actualidad, hay más de 900 residencias en 62 países, desde Irán hasta Bangladés.

Finanzas, tecnología y derecho

Podría parecer que las finanzas, la tecnología y el derecho son áreas que se interrelacionan menos con la creación de arte. Para muchos artistas, la naturaleza repetitiva de las tareas realizadas en trabajos diurnos puede, paradójicamente, estimular nuevas formas de pensar. Los descubrimientos artísticos suelen aparecer tanto en medio de las rutinas diarias como durante los dramas emocionales.

Para Ragen Moss, por ejemplo, las áreas en apariencia disímiles del arte y el derecho le ofrecen una especie de entrenamiento cruzado muy productivo. Tal como ella comenta, "tener un trabajo tan diferente (como es el de ejercer la abogacía), en vez de quitarme energía para hacer arte, parece que funciona como influencia contraintuitiva que beneficia el surgimiento de ideas creativas". Sus esculturas también revelan una conexión tangible con su trabajo de abogada, ya que suelen incluir textos de documentos legales.

VLM (Virginia L. Montgomery)

Las obras de VLM (Virginia L. Montgomery) presentadas dentro de la Galería de Cine y Video son parte de la gran exposición Day Jobs (Trabajos Diurnos), que se puede visitar en la Butler Gallery, en la planta baja del museo. VLM se describe a sí misma como una artista que “piensa en símbolos”. Durante más de una década, trabajó en el campo de representación gráfica, en la creación de conceptos para diversas situaciones, desde conferencias en el área del cuidado de la salud hasta el lanzamiento de una aplicación en el South by Southwest en Austin. La representación gráfica —un nicho que se desarrolló en el Área de la Bahía de San Francisco en la década de 1970— consiste en plasmar ideas en palabras e imágenes sobre pizarras blancas gigantes para que quienes participen puedan asimilar mejor el contenido que se está compartiendo.