In Creative Harmony: Three Artistic Partnerships

Sunday, February 16, 2025 - Sunday, July 20, 2025

Arshile Gorky and Isamu Noguchi

José Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodríguez

Nora Naranjo Morse and Eliza Naranjo Morse

No artist creates in isolation. Shared visual languages, techniques, and concerns shape artistic innovation.

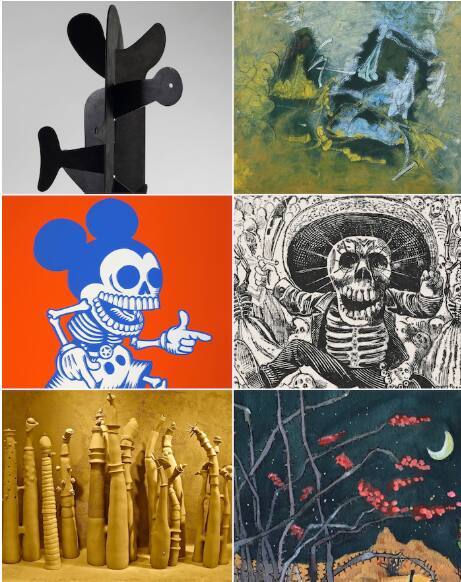

"In Creative Harmony" explores the ways in which artists inspire each other by highlighting the relationships between three pairs of artists: inter-generational Mexican printmakers José Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodríguez; friends and innovators in abstract painting and sculpture Arshile Gorky and Isamu Noguchi; and Nora Naranjo Morse and her daughter Eliza Naranjo Morse, who will be creating new work together for the first time.

This three-part exhibition—each partnership organized by a different Blanton curator—reveals the diversity of connections and contexts that drive creativity.

-Arshile Gorky and Isamu Noguchi: Outside In-

From the late 1920s through the 1940s, painter Arshile Gorky (circa 1904–1948) and sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) developed their distinctive abstract vocabularies grounded in the natural world or evoking organic forms. Simultaneously, the artists established a friendship informed not only by their work, but also by a shared sense of otherness. The tension between “outside” and “inside” structured their stylistic synthesis of nature, memory, and myth, as well as their national and ethnic identities, resulting in highly personal visual languages.

Outside In reunites for the first time the three known collaborative drawings Gorky and Noguchi produced with De Hirsh Margules in 1939 in response to the outbreak of war in Europe. It will also present works shown by Gorky and Noguchi in landmark exhibitions of the 1940s but not seen together in over 70 years. These works ground Gorky and Noguchi in their historical moment—between Surrealism and the emerging New York School—and reveal the originality and impact of their visions.

Organized by Claire Howard, Associate Curator, Collections and Exhibitions, Blanton Museum of Art

-José Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodríguez: Calaveras y Corazones-

Calaveras y Corazones explores a cross-generational conversation between two radical Mexican printmakers. Known as “The Mexican Goya,” José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) is also considered the father of modern Mexican printmaking. Inspired by Posada’s use of irony, satire, and caustic social critique as potent artistic strategies, Artemio Rodríguez (b. 1972) employs the same grim humor in works challenging contemporary social and political injustice.

Both Posada and Rodríguez depict imagined, sometimes apocalyptic, worlds where “all’s fair in love and war.” These two thematic throughlines connect their bodies of work with scenes of murderous skeletons and damsels in distress, often depicted as calaveras y corazones (“skulls and hearts/sweethearts”). This section will feature approximately 80 carefully chosen works, including many Posada prints drawn from Rodríguez’s personal collection and loans from esteemed institutions.

Organized by Vanessa Davidson, Curator of Latin American Art, Blanton Museum of Art

-Nora Naranjo Morse and Eliza Naranjo Morse: Lifelong-

For Lifelong, contemporary artists Nora Naranjo Morse (b. 1953) and Eliza Naranjo Morse (b. 1980), the mother-daughter descendants of a renowned artistic family of the Kha’p’o Owingeh (Santa Clara Pueblo, NM), are collectively creating an immersive environment. Together, they’ll merge their familial and personal artistic practices through artworks that center Indigenous ways of thinking about our relationship to the planet, the sacredness of life, and acts of creativity. Their new collaborative work is grounded in the materiality of their community, from the micaceous clay of Pueblo ceramicists to local found and recycled materials, all imbued with legacies of storytelling.

Working together at this scale for the first time, Nora and Eliza Naranjo Morse explore the deep roots of how materials and languages embody meaning, how images and forms narrate ancestral journeys and how art can help envision a better future for all of us.

Organized by Hannah Klemm, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Blanton Museum of Art

"In Creative Harmony: Three Artistic Partnerships" is organized by the Blanton Museum of Art.

Major support for this exhibition at the Blanton is provided by The Moody Foundation. This exhibition is supported in part by David and Ellen Berman.

Gallery TextJosé Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodríguez

Nora Naranjo Morse and Eliza Naranjo Morse

No artist creates in isolation. Shared visual languages, techniques, and concerns shape artistic innovation.

"In Creative Harmony" explores the ways in which artists inspire each other by highlighting the relationships between three pairs of artists: inter-generational Mexican printmakers José Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodríguez; friends and innovators in abstract painting and sculpture Arshile Gorky and Isamu Noguchi; and Nora Naranjo Morse and her daughter Eliza Naranjo Morse, who will be creating new work together for the first time.

This three-part exhibition—each partnership organized by a different Blanton curator—reveals the diversity of connections and contexts that drive creativity.

-Arshile Gorky and Isamu Noguchi: Outside In-

From the late 1920s through the 1940s, painter Arshile Gorky (circa 1904–1948) and sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) developed their distinctive abstract vocabularies grounded in the natural world or evoking organic forms. Simultaneously, the artists established a friendship informed not only by their work, but also by a shared sense of otherness. The tension between “outside” and “inside” structured their stylistic synthesis of nature, memory, and myth, as well as their national and ethnic identities, resulting in highly personal visual languages.

Outside In reunites for the first time the three known collaborative drawings Gorky and Noguchi produced with De Hirsh Margules in 1939 in response to the outbreak of war in Europe. It will also present works shown by Gorky and Noguchi in landmark exhibitions of the 1940s but not seen together in over 70 years. These works ground Gorky and Noguchi in their historical moment—between Surrealism and the emerging New York School—and reveal the originality and impact of their visions.

Organized by Claire Howard, Associate Curator, Collections and Exhibitions, Blanton Museum of Art

-José Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodríguez: Calaveras y Corazones-

Calaveras y Corazones explores a cross-generational conversation between two radical Mexican printmakers. Known as “The Mexican Goya,” José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) is also considered the father of modern Mexican printmaking. Inspired by Posada’s use of irony, satire, and caustic social critique as potent artistic strategies, Artemio Rodríguez (b. 1972) employs the same grim humor in works challenging contemporary social and political injustice.

Both Posada and Rodríguez depict imagined, sometimes apocalyptic, worlds where “all’s fair in love and war.” These two thematic throughlines connect their bodies of work with scenes of murderous skeletons and damsels in distress, often depicted as calaveras y corazones (“skulls and hearts/sweethearts”). This section will feature approximately 80 carefully chosen works, including many Posada prints drawn from Rodríguez’s personal collection and loans from esteemed institutions.

Organized by Vanessa Davidson, Curator of Latin American Art, Blanton Museum of Art

-Nora Naranjo Morse and Eliza Naranjo Morse: Lifelong-

For Lifelong, contemporary artists Nora Naranjo Morse (b. 1953) and Eliza Naranjo Morse (b. 1980), the mother-daughter descendants of a renowned artistic family of the Kha’p’o Owingeh (Santa Clara Pueblo, NM), are collectively creating an immersive environment. Together, they’ll merge their familial and personal artistic practices through artworks that center Indigenous ways of thinking about our relationship to the planet, the sacredness of life, and acts of creativity. Their new collaborative work is grounded in the materiality of their community, from the micaceous clay of Pueblo ceramicists to local found and recycled materials, all imbued with legacies of storytelling.

Working together at this scale for the first time, Nora and Eliza Naranjo Morse explore the deep roots of how materials and languages embody meaning, how images and forms narrate ancestral journeys and how art can help envision a better future for all of us.

Organized by Hannah Klemm, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Blanton Museum of Art

"In Creative Harmony: Three Artistic Partnerships" is organized by the Blanton Museum of Art.

Major support for this exhibition at the Blanton is provided by The Moody Foundation. This exhibition is supported in part by David and Ellen Berman.

Introduction

No artist develops a unique vision or style in isolation. New ideas may come from lived experience, experimenting with materials and forms, cultural traditions, or connections to other artists. This exhibition presents three pairs of artists to show how shared visual languages, techniques, and conceptual interests shape innovation. Featuring a range of dialogues, In Creative Harmony explores the varied effects of collaboration, connection, and legacy on artistic production. The works on display exemplify how the featured artists respond to their moment, their predecessors, and their communities.

José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) was known both as the “Mexican Goya” and as the “Printmaker of the People.” His work tempered caustic political critique and social satire with respect for community histories and traditions. One hundred years later, Posada’s graphic style and social commitments served as inspirations to his compatriot Artemio Rodríguez (b. 1972). Living in Los Angeles, Rodriguez embraced Posada’s foundational precedent to translate community ideals of resistance and social justice into graphic form. Rodríguez’s syncretic artistic language reflects a virtual dialogue with Posada, spanning a century.

In the 1930s and 1940s, painter Arshile Gorky (c. 1904–1948) and sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) developed distinctive abstract vocabularies grounded in the natural world. They also established a friendship informed not only by their work, but also by a shared sense of national dislocation and otherness. Their independent engagements with Surrealism and abstraction generated personal and highly original visual languages that had a profound impact on the development of twentieth-century American art.

Nora Naranjo Morse (b. 1953) and her daughter, Eliza Naranjo Morse (b. 1980), come from a long lineage of Kha’ p’o artists, a Tewa-speaking Pueblo community in northern New Mexico. They combine ancestral knowledge with contemporary global experience to create artworks that span time and cultures. Materials and languages imbue meaning in their work, as both artists draw on deep roots of shared stories and the exchange of knowledge to explore distinct modes of visual expression.

In the spirit of collaboration, each section of this exhibition is organized by an individual curator with a distinct perspective on partnership. Collectively, they explore the ways the creative spirit can be enriched by a shared aesthetic and conceptual approach to making art.

Arshile Gorky and Isamu Noguchi: Outside In

From the late 1920s through the 1940s, painter Arshile Gorky (circa 1904–1948) and sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) developed distinctive abstract vocabularies grounded in the natural world or evoking organic forms. At the same time, the artists established a friendship informed not only by their work, but also by a shared sense of national dislocation and otherness. The tension between outside and inside defines their highly personal visual languages, which reconcile nature, memory, and myth, and draw on their national and ethnic identities and independent engagements with Surrealism and abstraction.

Gorky and Noguchi’s friendship was fostered by similar experiences. Noguchi was born in Los Angeles to a white American mother and Japanese father, grew up in Japan, and would voluntarily enter a Japanese American incarceration camp during World War II. Gorky, born Vosdanig Adoian in an Armenian province of the Ottoman Empire, lost his mother in the Armenian Genocide before immigrating to the US as a teenager and later changing his name. Both men found themselves in New York in the 1920s, struggling to make a life and find a voice as an artist. As their friendship blossomed in the 1930s, they demonstrated increasing artistic confidence by experimenting with abstraction, even in the realist-leaning milieu of the Federal Art Project and public commissions.

By the mid-1940s, Gorky and Noguchi had each developed his signature style, often termed “biomorphic” abstraction for the suggestion of natural or anatomical forms found in Gorky’s sinuous lines and veils of color and Noguchi’s interlocking slab sculptures. The psychological inflection of these works aligned the artists with the Surrealists, with whom they exhibited in Paris and New York, and anticipated the rise of Abstract Expressionism. Nonetheless, the originality of Gorky’s and Noguchi’s visions and the experiences and identities that bonded them have ensured that they remain outside of easy categorization.

Experiments in Abstraction

In the 1930s, both Gorky and Noguchi developed their independent artistic identities through experimentation with abstraction. Gorky demonstrated an early interest in Surrealism in his mysterious arrangements of organic forms and objects in the compartmentalized compositions of his Nighttime, Enigma, and Nostalgia series. After visits to Paris, Russia, and China and an extended stay in Japan, in 1931 Noguchi returned to New York and to what he called “the same old problem of making a living.”

Like many of their peers, the two artists turned to public art commissions to sustain themselves during the Great Depression. While Gorky participated in the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, a government initiative to provide employment to artists, Noguchi pursued commissions from the New York City Parks Department and other agencies and businesses. Although many New Deal–era art projects utilized a figurative style thought best to communicate with the public, Gorky and Noguchi embraced abstraction in their proposals, often leading to rejection or criticism of their designs. Noguchi wanted “to find a way of sculpture that was humanly meaningful without being realistic, at once abstract and socially relevant.” Gorky provocatively condemned the dominant style of Social Realism as “poor art for poor people.”

It was also during this period that Gorky and Noguchi cemented their friendship, united by both their shared artistic commitments and sense of national alienation. “It was a kind of bond between us, not being entirely American,” Noguchi recalled. “We had a certain loneliness here, which we shared, and art was … the thing that kept us going.”

The Outbreak of War in Europe: Collaborative Drawings

On September 3, 1939, Gorky, Noguchi, and Romanian-born artist De Hirsh Margules (1899–1965) were together in Noguchi’s studio when they heard President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s radio address regarding the outbreak of war in Europe, two days after the Nazi invasion of Poland. In response, the artists produced at least four known collaborative drawings, using Noguchi’s preexisting drawings, crayon, pencil, India ink, and sealing wax. Three of these drawings are reunited here for the first time.

These layered, improvised compositions suggest the artists’ interpretation of the Surrealist “exquisite corpse,” a game in which multiple participants create a sentence or drawing without seeing the previous player’s contribution, creating unexpected juxtapositions of words and imagery via chance. The agitated lines and appearance of Gorky’s handprints in red sealing wax on one work also expresses the artists’ distress and anxiety in response to the rise of Nazism and the specter of wartime violence and displacement. Their antiwar statement was informed by all three artists’ distinct experiences of discrimination, xenophobia, and the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment in Depression-era New York. Gorky’s traumatic experience of the Armenian Genocide also made him pointedly aware of the stakes in this growing conflict.

Psychological Landscapes

The early 1940s represented a watershed—personally and creatively—for both artists, as they drew inspiration from nature, abstracting and imbuing their landscapes with psychological content. After a cross-country road trip with Gorky and his future wife, Agnes Magruder, Noguchi was living in California on December 7, 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, precipitating the US entry into World War II. The subsequent rise of anti-Asian bigotry galvanized Noguchi politically; in an act of solidarity with his fellow Japanese Americans, he voluntarily entered an incarceration camp in Poston, Arizona, in May 1942. After returning to New York that November, he began a series of relief sculptures in white magnesite, which he called Lunars. These works emerged from Noguchi’s time in the Arizona desert—which he compared to a moonscape—suggesting both a desire to escape to other realms and the feeling of being treated as “alien” in one’s own country.

In early 1944, Noguchi introduced Gorky to Surrealist leader André Breton who, with much of his group, had fled Paris after the Nazi occupation. In the paintings he made that year, Gorky melded direct observation of the Virginia countryside with the Surrealist interest in the unconscious, eroticism, and automatically generated imagery, treating nature, Breton wrote, “like a cryptogram.” The Virginia landscape released in Gorky memories of his Armenian childhood surroundings, which he expressed in seemingly improvisatory and deeply personal abstractions featuring washes of color, flowing lines, and hybrid imagery.

The Biomorphic 1940s

This section reunites four works that Gorky and Noguchi showed in two important New York exhibitions to contextualize their nature-based abstraction in the mid-1940s. Their contact with leading members of the Surrealist group in New York during World War II inspired many American artists to embrace automatic drawing and other means of liberating the unconscious. Gorky, Noguchi, and several others gave significant representation to biomorphic abstraction amid the wide range of artistic styles in Fourteen Americans, the Museum of Modern Art’s eclectic 1946 survey of contemporary American art.

In 1947, Gorky and Noguchi appeared in Bloodflames, an exhibition at the Hugo Gallery curated by Surrealist poet and critic Nicolas Calas. It featured eight artists who extended the biomorphic vocabulary of earlier Surrealists such as Jean Arp or André Masson, infusing their forms with a primordial, mythic quality that echoed postwar realities. Later that year, Gorky and Noguchi were two of only a few Americans included in the Surrealists’ international exhibition in Paris; Gorky exhibited two paintings and Noguchi showed Monument to Heroes, as well as Time Lock and Lunar Landscape (Woman), both on view nearby.

As Abstract Expressionist painting came to dominate the American art scene in the late 1940s and 1950s, an emphasis on formal qualities and gestural brushwork eclipsed the evocative, organic forms showcased in Fourteen Americans and Bloodflames, and critics downplayed the influence of Surrealism’s interest in the unconscious. After his death in 1948, Gorky was claimed as an early Abstract Expressionist, despite his lifetime engagement with Surrealism. Likewise, critics’ awareness of Noguchi’s own cultural hybridity often limited their readings of his biomorphic forms, which they assumed reflected a fusion of East and West.

José Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodríguez: Calaveras y Corazones

“My encounter with José Guadalupe Posada’s unique prints made me comprehend that it was indeed possible to become an artist in every sense of the word through printmaking. This certainty opened my eyes and helped me focus entirely on this vocation.”

— Artemio Rodríguez

In this exhibition, two masterful Mexican printmakers engage in a visual dialogue across the span of a century. Both employ political critique and social satire, while, on the other hand, also celebrating their communities’ popular tales and traditions. Working in Mexico City at the turn of the twentieth century, José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) was known as the “Printmaker of the People” as well as the “Mexican Goya.” Artemio Rodríguez (b. 1972) first flourished as an artist while living in the United States from 1994 to 2008. He embraced Posada’s foundational precedent as a bridge to Chicano artists’ own strategies to graphically represent their socio-political context. Splicing narrative lessons learned from Posada with elements of Chicano and medieval European visual cultures, Rodríguez creates a syncretic art that expands Posada’s legacy into other art histories, other worlds.

Anchored within each artist’s respective contemporary milieu, the themes of Celebration and Satire structure this exhibition. These foundational through-lines serve as elastic platforms connecting the two artists’ diverse production. Posada and Rodríguez both shared a profound respect for communal heritage and beloved community traditions. They also raucously raise the dead into living, mischievous, satirical calaveras (skeletons): vehicles for grim humor, biting irony, and socio-political parody. Ultimately, each artist embraces and examines the popular culture of his particular place and time, utilizing parallel narrative tactics that unite them. The first exhibition to explore Posada’s and Rodríguez’s virtual partnership, Calaveras y Corazones spotlights channels of inspiration and hybrid strains of innovation that run deep, despite living in different eras.

Decisive Historical Moments: 100 Years and A World Apart

This exhibition visually situates José Guadalupe Posada (Aguascalientes, Mexico, 1852–Mexico City, 1913) and Artemio Rodríguez (Tacámbaro, Mexico, 1972–Páztcuaro, Mexico, present) in distinct, yet decisive historical moments. From both sides of the Mexico/United States border, they examine the evolving, fluctuating relationship between these two countries, each embracing socio-political parody and calavera iconography as critical tools to depict their communities’ realities a century ago, and today.

José Guadalupe Posada’s Era

Posada was active during the long years of the Porfiriato, Porfirio Díaz’s repressive dictatorial regime (1884–1911), eventually overthrown by the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). During this period, the Mexican-American War (1846–1848) was in recent memory, as was the subsequent U.S. annexation of 500,000 square miles of Mexican territory. To facilitate the growth of these newly acquired lands in today’s American Southwest, agents from the U.S. railroad, mining, and agricultural industries appealed to Mexican laborers—afflicted by low wages and the civil war—to cross the border to work. Posada only lived to see the first three years of the Revolution, but he was an astute witness to the roiling socio-political tensions that preceded it, which he documented raw upon the page.

Artemio Rodríguez’s Era

A century after Posada, in his work Rodríguez documented life in the country he parodied as “Freedomland” from an immigrant’s perspective: from the outside, looking in. His U.S. sojourn from 1994 to 2008 coincided with the aftermath of the first conflict in the Persian Gulf (1990-1991), the onset of the Second Gulf War (2003-2011), and the U.S.’s 1995 Immigration Reform Act, which increased requirements for immigrants. He found his artistic voice in California, where Chicano artists and their communities embraced him. Anchored in their daily struggles, triumphs, popular traditions, and shared heritage, as well as this overarching context, Rodríguez depicts a version of the “American Dream” rooted in popular culture at an historical crossroad.

Satire: Calaveras and the Triumph of Death

The artworks in this section spotlight José Guadalupe Posada’s and Artemio Rodríguez’s shared penchant for socio-political critique. Images range from machete-wielding calaveras and sensationalized apocalyptic scenes, to satirical caricatures of political figures. Reflecting both dark humor and dry wit, Rodríguez even audaciously kills off pop culture icons Mickey Mouse and Superman, turning them into the calaveras Mickey Muerto and Supermuerto —just as Posada himself had daringly done with politicians in his own satirical portraits.

Posada first popularized his calaveras as ironic depictions of the Mexican bourgeoisie beginning in the mid-1890s. Inspired as much by pre-Columbian artforms as by popular Day of the Dead traditions, Posada’s skeletal figures unexpectedly enjoyed great popularity and renown as they evolved instead into beloved, everyday characters fighting for the underdog. Today, Posada’s most famous creations, such as the demure Calavera Catrina and the revolutionary Skeleton from Oaxaca, belong to global popular culture, while also serving among Mexican and Chicano communities as symbols of shared heritage and icons for overcoming adversity. Rodríguez’s calaveras turn fiercer in his tour-de-force “print mural” The Triumph of Death, a reinterpretation of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s original 1562 painting, which graphically illustrates Rodríguez’s syncretic fusion of inspiration derived from Posada with other art historical traditions.

Celebration: Community and Culture

José Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodríguez both evoke devotion to local traditions and common histories in their prolific prints. Posada’s imagery of community celebration centered on his calaveras, those beloved characters enacting rituals of popular life and lore. Although rooted in a different time, Rodríguez similarly embraces popular Mexican and Chicano popular cultures, reframing scenes of everyday life into narratives of cultural affirmation, which often empower women or satirically underscore discrimination against them. In addition, the images paired here graphically illustrate disparities in gender relations and women’s liberties from each artist’s era.

Mother-daughter artists Nora Naranjo Morse (b. 1953) and Eliza Naranjo Morse (b. 1980) have inherited methods for creative expression from generations of Kha’ p’o ancestry, a Tewa-speaking Pueblo community in northern New Mexico. These methods are woven with their contemporary global experience into artwork that considers relationships to the land, life, and the connective spirit that exists as a potential form of empowerment.

For Nora and Eliza, art embodies a curious, collaborative, and creative spirit. The figures, images, and narratives represented in these works are imbued with legacies of ancestral, familial, and personal storytelling. The physical forms are grounded in the materiality of their community—from the micaceous clay used for centuries by Pueblo ceramicists to locally found and recycled materials.

Nora’s three sculptures, We Come with Stories, are made from this local clay. Inspired by traditional Tewa Pueblo pottery techniques, each figure is a symbol of a cultural worldview that connects humans to their environment through the power of storytelling. Eliza’s paintings in the exhibition depict vibrant, detailed renderings of anthropomorphized animals engaged in journeys, rituals, and labor. Her lexicon of images is inspired by her family, community, and the popular culture she saw as a child. As she says of the work, “It’s playful, it’s both serious and not serious, and sometimes it doesn’t look serious but is describing serious things.”

Collaboration is a central tenet of the exhibition. According to Nora, “[It] is an exchange, a trust of shared ideas that opens the door to the unexpected—igniting imagination and a collective expression—whatever form that working together takes.” This act of collaborating is uniquely articulated in a series titled Pass It. To create these works, mother and daughter passed a drawing back and forth, building on the marks the other had made.

Throughout the gallery, each piece contributes to a dynamic dialogue that spans time and cultures and the sharing of aesthetic sensibilities to tell an ongoing story. They showcase the deep roots of exchanged knowledge systems, how images and forms narrate ancestral journeys, and how art helps envision a proactive engagement in our future.

Introducción

Ningún artista desarrolla una visión o estilo único en aislamiento. Sus nuevas ideas pueden surgir de experiencias vividas, de la experimentación con materiales y formas, o de tradiciones culturales o conexiones con otros artistas. Esta exposición presenta tres duplas de artistas para mostrar cómo los lenguajes visuales, las técnicas y los intereses conceptuales compartidos dan forma a la innovación. Presentando una variedad de diálogos, En armonía creativa explora los efectos diversos de la colaboración, la conexión y el legado en la producción artística. Las obras exhibidas ejemplifican cómo los artistas aquí presentados responden a su momento, a sus predecesores y a sus comunidades.

José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) fue conocido como el "Grabador del Pueblo" pero también como el "Goya Mexicano." Su obra equilibró una crítica política mordaz y una sátira social con respeto por las historias y tradiciones comunitarias. Cien años después, el estilo gráfico y los compromisos sociales de Posada sirvieron de inspiración para su compatriota Artemio Rodríguez (n. 1972). Mientras vivía en Los Ángeles, Rodríguez adoptó el precedente fundamental de Posada para traducir los ideales comunitarios de resistencia y justicia social en forma gráfica. Con un siglo de distancia, el lenguaje artístico sincrético de Rodríguez refleja un diálogo virtual con Posada.

En las décadas de 1930 y 1940, el pintor Arshile Gorky (c. 1904–1948) y el escultor Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) desarrollaron vocabularios abstractos distintivos arraigados en el mundo natural. Establecieron una amistad basada no sólo en su trabajo, sino también en un sentido compartido de desarraigo nacional y de otredad. Sus compromisos independientes con el surrealismo y la abstracción generaron lenguajes visuales personales y profundamente originales que tuvieron un impacto significativo en el desarrollo del arte estadounidense del siglo XX.

Nora Naranjo Morse (n. 1953) y su hija, Eliza Naranjo Morse (n. 1980), provienen de un largo linaje de artistas Kha’ p’o, una comunidad Pueblo de habla Tewa en el norte de Nuevo México. Ambas combinan conocimientos ancestrales con experiencias globales contemporáneas para crear obras de arte que conectan tiempos y culturas. Los materiales y lenguajes aportan significado a su trabajo, ya que las dos artistas recurren a profundas raíces de historias compartidas y al intercambio de conocimientos para explorar modos distintos de expresión visual.

En el espíritu de la colaboración, cada sección de esta muestra está a cargo de una curadora diferente, aportando una perspectiva distinta sobre el trabajo colectivo. Como grupo, las tres exploran las formas en las que el espíritu creativo puede enriquecerse mediante un enfoque estético y conceptual compartido.

Arshile Gorky e Isamu Noguchi: De afuera hacia adentro

Desde finales de los años veinte hasta los años cuarenta, el pintor Arshile Gorky (c. 1904-1948) y el escultor Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) desarrollaron vocabularios abstractos propios, basados en el mundo natural y la evocación de formas orgánicas. Al mismo tiempo, los artistas establecieron una amistad influenciada no sólo por su trabajo, sino también por un sentido compartido de desplazamiento nacional y alteridad. La tensión entre el exterior y el interior define sus lenguajes visuales profundamente personales, que concilian naturaleza, memoria y mito, y se inspiran en sus identidades nacionales y étnicas, así como en sus exploraciones individuales del surrealismo y la abstracción.

La amistad entre Gorky y Noguchi fue nutrida por experiencias similares. Noguchi nació en Los Ángeles de una madre estadounidense blanca y un padre japonés, creció en Japón y entró voluntariamente en un campo de reclusión para japoneses americanos durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Gorky, nacido como Vosdanig Adoian en una provincia armenia del Imperio Otomano, perdió a su madre en el genocidio armenio antes de emigrar a los Estados Unidos como adolescente donde más tarde cambiaría su nombre. Los dos se conocieron en Nueva York en la década de 1920, luchando por construir una vida y encontrar su voz como artistas. A medida que su amistad germinó durante los años treinta, demostraron una creciente confianza artística al experimentar con la abstracción, aún cuando el Federal Art Project [Proyecto Federal de Arte] y las comisiones públicas preferían el realismo.

A mediados de los años cuarenta, tanto Gorky como Noguchi habían desarrollado su estilo característico, a menudo denominado abstracción “biomórfica” por la sugerencia de formas naturales o anatómicas presentes en las sinuosas líneas y velos de color de Gorky y en las esculturas de losas entrelazadas de Noguchi. La inclinación psicológica de estas obras acercó a los artistas con los surrealistas, con quienes expusieron en París y Nueva York, y anticipó el surgimiento del expresionismo abstracto. Sin embargo, la originalidad de las visiones de Gorky y Noguchi, así como las experiencias e identidades que los unieron, los han mantenido fuera de categorizaciones fáciles.

Experimentos en abstracción

En la década de 1930, tanto Gorky como Noguchi desarrollaron sus identidades artísticas independientes mediante la experimentación con la abstracción. Gorky mostró un interés temprano por el surrealismo, visible en sus enigmáticas composiciones de formas y objetos orgánicos dispuestos en sus series Nocturno, Enigma y Nostalgia. Después de visitar París, Rusia y China, así como una estancia prolongada en Japón, Noguchi retornó a Nueva York en 1931 para volver a enfrentarse a lo que él llamó, “el mismo viejo problema de ganarse la vida”.

Como muchos de sus colegas, ambos artistas realizaron comisiones de arte público para solventarse durante la Gran Depresión. Mientras Gorky participó en el Proyecto Federal de Arte de la Administración de Obras Públicas, una iniciativa gubernamental para dar empleo a artistas, Noguchi hizo comisiones para el Departamento de Parques de la Ciudad de Nueva York y otras instituciones y empresas. Aunque muchos proyectos artísticos de la era del New Deal se valieron de un estilo figurativo —considerado más apropiado para comunicarse con el público—, Gorky y Noguchi adoptaron la abstracción en sus propuestas, conduciendo al rechazo o la crítica de sus diseños en varias ocasiones. Noguchi quería “encontrar una manera de hacer escultura que fuera significativa humanamente sin ser realista, a la vez abstracta y socialmente relevante”. Gorky condenó provocativamente el estilo dominante del realismo social como “arte pobre para gente pobre”.

Fue también durante este período cuando Gorky y Noguchi consolidaron su amistad, unida tanto por sus compromisos artísticos compartidos como por un sentido de alienación nacional. “Había un tipo de vínculo entre nosotros por no ser completamente estadounidenses”, recordó Noguchi. “Aquí compartíamos una cierta soledad y el arte fue… algo que nos mantuvo en pie”.

El estallido de la guerra en Europa: los dibujos colaborativos

El 3 de septiembre de 1939, Gorky, Noguchi y el artista rumano De Hirsh Margules (1899–1965) estaban juntos en el estudio de Noguchi cuando escucharon el discurso en la radio del presidente Franklin D. Roosevelt sobre el estallido de la guerra en Europa, justo dos días después de la invasión nazi a Polonia. En respuesta, los artistas produjeron al menos cuatro dibujos colaborativos, utilizando dibujos preexistentes de Noguchi, crayón, lápiz, tinta india y lacre. Tres de estos dibujos se reúnen por primera vez en esta sala.

Estas composiciones improvisadas y en capas sugieren la interpretación que los artistas hicieron del “cadáver exquisito” surrealista, un juego en el que varios participantes crean una frase o un dibujo sin ver la contribución anterior, generando yuxtaposiciones inesperadas de palabras e imágenes por medio del azar. Las líneas agitadas y la presencia de huellas de Gorky en lacre rojo, visibles en una de las obras, también expresan la angustia y ansiedad de los artistas frente al ascenso del nazismo y el espectro de la violencia y el desplazamiento bélico. Su declaración contra la guerra se basó en las experiencias particulares de los tres artistas con la discriminación, la xenofobia y el aumento de un sentimiento antiinmigrante en Nueva York durante la Depresión. La experiencia traumática de Gorky en el genocidio armenio lo hizo especialmente consciente de lo que estaba en juego con este creciente conflicto.

Paisajes psicológicos

El principio de los años cuarenta marcó un punto de inflexión personal y creativo para ambos artistas, quienes se inspiraron en la naturaleza, y abstrajeron e impregnaron sus paisajes con contenido psicológico. Noguchi se estableció en California después de hacer un viaje por carretera de costa a costa con Gorky y Agnes Magruder, quienes luego se casarían. Allí estaba el 7 de diciembre de 1941, cuando Japón atacó Pearl Harbor, anticipando la entrada de Estados Unidos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial. El aumento del prejuicio anti-asiático que se desencadenó como consecuencia galvanizó a Noguchi políticamente: en un acto de solidaridad con sus compañeros japoneses americanos, ingresó voluntariamente a un campo de reclusión en Poston, Arizona, en mayo de 1942. Después de regresar a Nueva York en noviembre de 1942, Noguchi comenzó una serie de esculturas en relieve de magnesita blanca que llamó Lunarios. Estas obras surgieron del tiempo que pasó en el desierto de Arizona —al cual que comparó con un paisaje lunar— y sugieren tanto un deseo de escapar a otros mundos como el sentimiento de ser tratado como un “extranjero” en su propio país.

A principios de 1944, Noguchi presentó a Gorky al líder surrealista André Breton, quien, junto con gran parte de su grupo, había huido de París tras la ocupación nazi. Las pinturas que Gorky realizó ese año fusionaron la observación directa del paisaje de Virginia con el interés surrealista en el inconsciente, el erotismo y las imágenes generadas automáticamente, tratando la naturaleza “como un criptograma”, en palabras de Breton. El paisaje de Virginia despertó en Gorky recuerdos de los alrededores de su infancia armenia, los cuales expresó en abstracciones aparentemente improvisadas y profundamente personales, con veladuras de color, líneas fluidas e imágenes híbridas.

Los años biomórficos de la década de 1940

Esta sección reúne cuatro obras que Gorky y Noguchi mostraron en dos importantes exposiciones en Nueva York, para contextualizar su abstracción basada en la naturaleza a mediados de los años cuarenta. Su contacto con destacados miembros del grupo surrealista en Nueva York durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial inspiró a muchos artistas estadounidenses a adoptar el dibujo automático y otros medios para liberar el inconsciente. Gorky, Noguchi y varios colegas representaron significativamente la abstracción biomórfica a través de una amplia gama de estilos artísticos en Catorce estadounidenses, la ecléctica exposición de arte contemporáneo estadounidense realizada en el Museo de Arte Moderno durante 1946.

En 1947, Gorky y Noguchi participaron en Llamas de sangre, una exposición en la Galería Hugo organizada por el poeta surrealista y crítico Nicolas Calas. En ésta se incluyeron ocho artistas que ampliaron el vocabulario biomórfico de los primeros surrealistas como Jean Arp o André Masson, fusionando sus formas con un misticismo que evocaba las realidades de la posguerra. Más tarde ese año, Gorky y Noguchi fueron dos de los pocos estadounidenses incluidos en la exposición internacional de surrealistas en París. Gorky exhibió dos pinturas y Noguchi presentó Monumento a los héroes, así como Bloqueo del tiempo y Paisaje lunar (Mujer), estas dos últimas incluidas en esta sala.

A medida que la pintura expresionista abstracta llegó a dominar la escena artística estadounidense a fines de los años cuarenta y en la década del cincuenta, tanto el énfasis en las cualidades formales como el gesto pictórico eclipsaron las formas orgánicas evocadoras visibles en Catorce estadounidenses y Llamas de sangre. Los críticos también minimizaron la influencia del interés surrealista en el inconsciente. Tras su muerte en 1948, Gorky fue considerado como un precursor del expresionismo abstracto, a pesar de su compromiso de por vida con el surrealismo. Asimismo, la percepción de la hibridación cultural de Noguchi limitó frecuentemente la interpretación de sus formas biomórficas, las cuales los críticos asumieron como una fusión de Oriente y Occidente.

José Guadalupe Posada and Artemio Rodriguez: Calaveras y Corazones

"My encounter with José Guadalupe Posada's unique prints made me comprehend that it was indeed possible to become an artist in every sense of the word through printmaking. This certainty opened my eyes and helped me focus entirely on this vocation." – Artemio Rodríguez

En esta exposición, dos maestros grabadores mexicanos entablan un diálogo visual a la distancia de un siglo. Ambos emplean la crítica política y la sátira social, mientras que también celebran los relatos populares y las tradiciones de sus comunidades. Trabajando en la Ciudad de México a finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX, José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) fue conocido como el “Grabador del Pueblo” y también como el “Goya Mexicano”. Por su parte, Artemio Rodríguez (n. 1972), se desarrolló como artista cuando vivió en Estados Unidos entre 1994 y 2008. Adoptó el legado fundacional de Posada como un puente hacia las estrategias de los artistas chicanos para representar gráficamente su contexto sociopolítico. Combinando las lecciones narrativas aprendidas de Posada con elementos de las culturas visuales chicana y de la Europa medieval, Rodríguez crea un arte sincrético que expande el legado de Posada hacia otras historias del arte y otros mundos.

Esta exposición se estructura en dos temas: Celebración y Sátira, ambos anclados en el respectivo contexto contemporáneo de cada artista. Estos ejes fundamentales sirven como plataforma elástica que conecta su respectiva producción plástica. Posada y Rodríguez comparten un profundo respeto por el patrimonio comunitario y las tradiciones más queridas de sus comunidades. También resucitan a los muertos para convertirlos en calaveras vivientes, traviesas y satíricas: vehículos para el humor negro, la ironía mordaz y la parodia sociopolítica. En última instancia, cada artista adopta y examina la cultura popular de su lugar y época particulares, ambos utilizando estrategias narrativas paralelas que los unen. Calaveras y Corazones es la primera exposición que explora el diálogo virtual entre Posada y Rodríguez, y pone de relieve los profundos canales de inspiración y las corrientes híbridas de innovación que calan hondo, aunque viviesen en distintas épocas.

La época de José Guadalupe Posada

Posada estuvo activo durante los largos años del Porfiriato, el represivo régimen dictatorial de Porfirio Díaz (1884-1911), derrocado finalmente por la Revolución Mexicana (1910-1920). Durante este periodo, la guerra mexicano-estadounidense (1846-1848) seguía en la memoria reciente, al igual que la posterior anexión de 500.000 millas cuadradas de territorio mexicano a los Estados Unidos. Para facilitar el crecimiento de estas tierras recién adquiridas en lo que hoy es el suroeste norteamericano, agentes de las industrias ferroviarias, mineras y agrícolas atraían a mexicanos— afectados por salarios bajos y la guerra civil—a cruzar la frontera para trabajar. Los periódicos populares mexicanos ilustrados por Posada advertían a los lectores de los peligros potenciales a los que se enfrentarían en el país que el artista satirizó como “Yankilandia”, como los salarios reducidos, las posibles deportaciones y la discriminación. Posada sólo vivió los tres primeros años de la Revolución, pero fue un testigo astuto de las tensiones sociopolíticas que la precedieron documentándolas crudamente en la página.

La época de Artemio Rodríguez

Un siglo después de Posada, Rodríguez documentó en su obra la vida en el país al que llamaba “Freedomland” desde la perspectiva de un inmigrante, mirando desde fuera hacia dentro. Su estancia en Estados Unidos entre 1994 y 2008 coincidió con las secuelas del primer conflicto del Golfo Pérsico (1990-1991), el inicio de la Segunda Guerra del Golfo (2003- 2011) y la Ley de Reforma de la Inmigración de 1995, la cual aumentaba los requisitos para los inmigrantes. Rodríguez encontró su voz artística en California, donde las comunidades de los artistas chicanos le acogieron. Anclado en sus luchas cotidianas, sus triunfos, sus tradiciones populares y su patrimonio común, así como en este contexto general, Rodríguez describe una versión del llamado “sueño americano” arraigada en la cultura popular de un momento histórico.

Momentos históricos decisivos: A 100 años y un mundo de distancia

Esta exposición sitúa visualmente a José Guadalupe Posada (Aguascalientes, México, 1852–Ciudad de México, 1913) y Artemio Rodríguez (Tacámbaro, México, 1972–Pátzcuaro, México, presente) en momentos históricos distintos pero igualmente decisivos. Desde ambos lados de la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos, ellos examinan la relación cambiante y fluctuante entre estos dos países, y cada uno de ellos adopta la parodia sociopolítica y la iconografía de la calavera como herramientas fundamentales para describir las realidades de sus comunidades separadas por un siglo.

La época de José Guadalupe Posada

Posada estuvo activo durante los largos años del Porfiriato, el represivo régimen dictatorial de Porfirio Díaz (1884-1911), derrocado finalmente por la Revolución Mexicana (1910-1920). Durante este periodo, la guerra mexicano-estadounidense (1846-1848) seguía en la memoria reciente, al igual que la posterior anexión de 500.000 millas cuadradas de territorio mexicano a los Estados Unidos. Para facilitar el crecimiento de estas tierras recién adquiridas en lo que hoy es el suroeste norteamericano, agentes de las industrias ferroviarias, mineras y agrícolas atraían a mexicanos— afectados por salarios bajos y la guerra civil—a cruzar la frontera para trabajar. Los periódicos populares mexicanos ilustrados por Posada advertían a los lectores de los peligros potenciales a los que se enfrentarían en el país que el artista satirizó como “Yankilandia”, como los salarios reducidos, las posibles deportaciones y la discriminación. Posada sólo vivió los tres primeros años de la Revolución, pero fue un testigo astuto de las tensiones sociopolíticas que la precedieron documentándolas crudamente en la página.

La época de Artemio Rodríguez

Un siglo después de Posada, Rodríguez documentó en su obra la vida en el país al que llamaba “Freedomland” desde la perspectiva de un inmigrante, mirando desde fuera hacia dentro. Su estancia en Estados Unidos entre 1994 y 2008 coincidió con las secuelas del primer conflicto del Golfo Pérsico (1990-1991), el inicio de la Segunda Guerra del Golfo (2003- 2011) y la Ley de Reforma de la Inmigración de 1995, la cual aumentaba los requisitos para los inmigrantes. Rodríguez encontró su voz artística en California, donde las comunidades de los artistas chicanos le acogieron. Anclado en sus luchas cotidianas, sus triunfos, sus tradiciones populares y su patrimonio común, así como en este contexto general, Rodríguez describe una versión del llamado “sueño americano” arraigada en la cultura popular de un momento histórico.

Sátira: Calaveras y El triunfo de la Muerte

Las obras de esta sección ponen de relieve el interés común de José Guadalupe Posada y Artemio Rodríguez por la crítica sociopolítica. Las imágenes oscilan entre calaveras armadas con machetes y escenas apocalípticas sensacionalizadas, hasta caricaturas satíricas de figuras políticas. Reflejando el humor negro y la ironía seca que ambos artistas comparten, Rodríguez audazmente “asesina” a íconos de la cultura pop como Mickey Mouse y Superman, transformándolos en las calaveras Mickey Muerto y Supermuerto, tal como Posada había hecho con políticos y burgueses mexicanos de su época en sus propios retratos satíricos.

Posada comenzó a popularizar sus calaveras como representaciones irónicas de la burguesía mexicana a mediados de la década de 1890. Inspiradas tanto en las formas artísticas precolombinas como en las tradiciones populares del Día de Muertos, las figuras esqueléticas de Posada disfrutaron inesperadamente de gran popularidad y renombre, evolucionando en cambio hacia personajes queridos y cotidianos que luchan por los desamparados. Hoy, las creaciones más famosas de Posada, como la Catrina recatada y el Esqueleto de Oaxaca revolucionario, pertenecen a la cultura popular global y, al mismo tiempo sirven entre las comunidades mexicanas y chicanas como símbolos de herencia compartida e íconos de superación ante la adversidad. Las calaveras de Rodríguez se vuelven más feroces en el espectacular mural impreso, El triunfo de la Muerte, una reinterpretación del cuadro original de Pieter Bruegel el Viejo de 1562, que ilustra gráficamente la fusión sincrética que hace Rodríguez de la inspiración derivada de Posada con otras tradiciones artísticas históricas.

Celebración: Comunidad y cultura

Celebración: Comunidad y cultura

Toda una vida: Nora Naranjo Morse y Eliza Naranjo Morse

Nora Naranjo Morse (n. 1953) y su hija Eliza Naranjo Morse (n. 1980) son una dupla de artistas que han heredado métodos para la expresión creativa de sus ancestros Kha’ p’o, una comunidad Pueblo de habla Tewa ubicada al norte de Nuevo México. Estos métodos se entretejen con su experiencia global contemporánea en obras de arte que consideran las relaciones con la tierra y la vida, así como con el espíritu conector que existe como una forma potencial de empoderamiento.

Para Nora y para Eliza, el arte encarna un espíritu creativo, curioso y colaborativo. Las figuras, imágenes y narrativas representadas en sus obras están impregnadas con los legados de narraciones ancestrales, familiares y personales. Las formas físicas están basadas en la materialidad de su comunidad —desde la arcilla micácea utilizada desde hace siglos por ceramistas Pueblo, hasta materiales locales encontrados y reciclados.

Las tres esculturas de Nora, Venimos con historias, están hechas de esta arcilla local. Inspiradas en las técnicas de cerámica tradicionales del pueblo Tewa, cada figura es el símbolo de una cosmovisión cultural que conecta a los humanos con su entorno a través del poder de la narrativa. Las pinturas de Eliza en la exposición representan imágenes vibrantes y detalladas de animales antropomorfizados que realizan viajes, rituales y labores. Su lenguaje de imágenes está inspirado en su familia, comunidad y la cultura popular a la que estuvo expuesta en su niñez. Como comenta la artista sobre su trabajo, “es juguetón; es serio pero al mismo tiempo no lo es y, a veces, no se ve serio pero da cuenta de cosas serias”.

La colaboración es el eje medular de esta muestra. Según Nora, “es un intercambio, una apuesta por ideas compartidas que abren la puerta hacia lo inesperado —incitando la imaginación y la expresión colectiva— hacia cualquier forma que tome el trabajo colaborativo”. Este acto de cooperación es articulado de manera particular en la serie titulada Pásalo. Para crear estas piezas, madre e hija se pasaron un dibujo de ida y vuelta, construyendo sobre los registros que la otra había realizado.

A través de la sala, cada obra contribuye a un diálogo dinámico que atraviesa tiempos y culturas, compartiendo sensibilidades estéticas para contar una historia que aún no termina. Las piezas muestran las raíces profundas de los sistemas de intercambio de saberes, la manera en que las imágenes y las formas narran viajes ancestrales y cómo el arte ayuda a visualizar una participación proactiva en nuestro futuro.