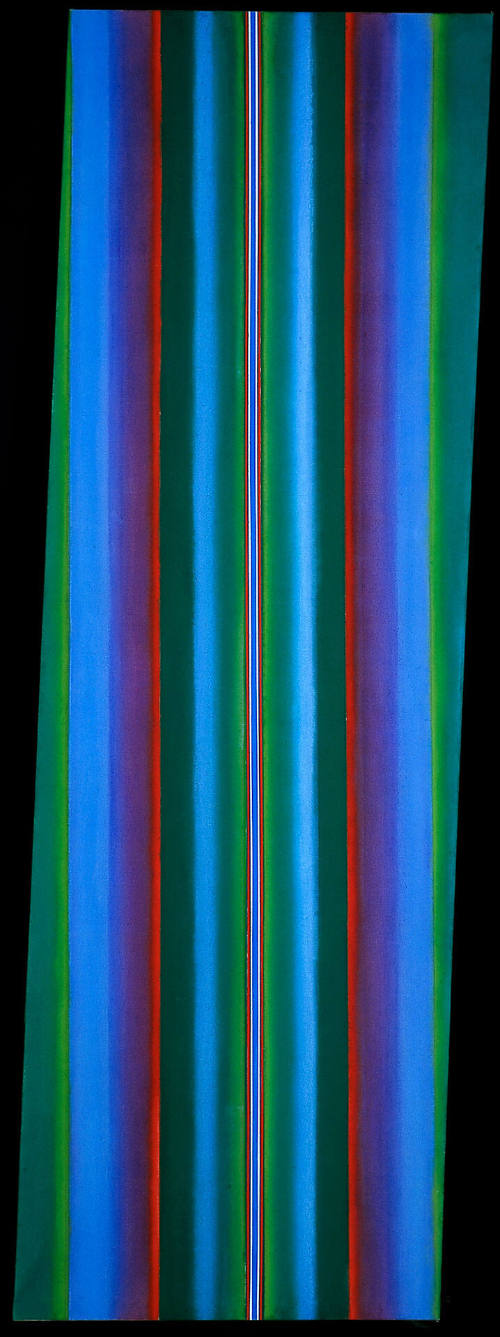

Oblique #9

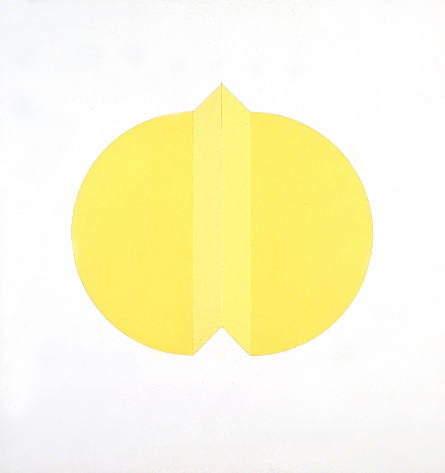

Primary

Leon Berkowitz

(Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1911–Washington, D.C., 1987)

NationalityAmerican, North America

Date1969

MediumAcrylic - resin on canvas on canvas

DimensionsCanvas: 113 3/8 x 37 in. (288 x 94 cm)

Credit LineBlanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Mari and James A. Michener, 1979.22

Keywords

Rights Statement

Collection AreaModern and Contemporary Art

Object number1979.22

On View

Not on viewCritics have long recognized Leon Berkowitz as one of the driving forces behind the development of abstract painting in the 1960s. As co-founder of the Washington Workshop Center for the Arts, which he established in 1945 with the help of his wife, the poet Ida Fox, Berkowitz played an instrumental role in the Washington Color School, a group of painters that included Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Howard Mehring among others.

For most of his career, Berkowitz was preoccupied with investigating the optical, visceral, and ultimately spiritual effects of color and light. Often reticent about discussing his technique, Berkowitz experimented with staining his canvases before he honed his mature method, which involved priming his canvases and then applying several thin layers of pigment. In 1955, Berkowitz and Fox embarked on a decade-long series of travels to Spain, Wales, Greece, Israel, and the American West, an experience that greatly affected Berkowitz’s work of the 1960s. Berkowitz also found inspiration in sources such as poetry, Eastern music and mysticism, and the psychology and biology of vision.

Oblique #9 typifies Berkowitz’s work from the 1960s. It is bisected by a blue stripe (what Berkowitz referred to as the painting’s “spine”) that divides the canvas into roughly two equal halves. On either side of the “spine” Berkowitz added vertical bands of color that gradually widen as they approach the edge of the canvas. Both the bands and the canvas form parallelograms, albeit parallelograms that lean in opposite directions, imparting to the work a sensation of tension and slight disequilibrium. The edges of the outermost bands bleed into one another, which, along with the thin layers of pigment, create a halo-like effect reminiscent of Dan Flavin’s fluorescent light sculptures. Not only do the bands appear to glow as if illuminated from within, they seem to float, unmoored, in front of the canvas.

In 1969, at the peak of the psychedelic age, Berkowitz’s one-person exhibition at the Corcoran Museum of Art in Washington, DC elicited an enthusiastic response from the public. A large group of hippies descended upon the opening of the show; they danced, sang, lay on the floors, and even requested that one painting be cut into small pieces and distributed to visitors. Although Berkowitz maintained that he was no mystic, he did believe that his paintings had the ability to evoke a spiritual response or an altered state of consciousness in the viewer. As he once stated, “I’m to alter human minds, as a life ambition."

Exhibitions