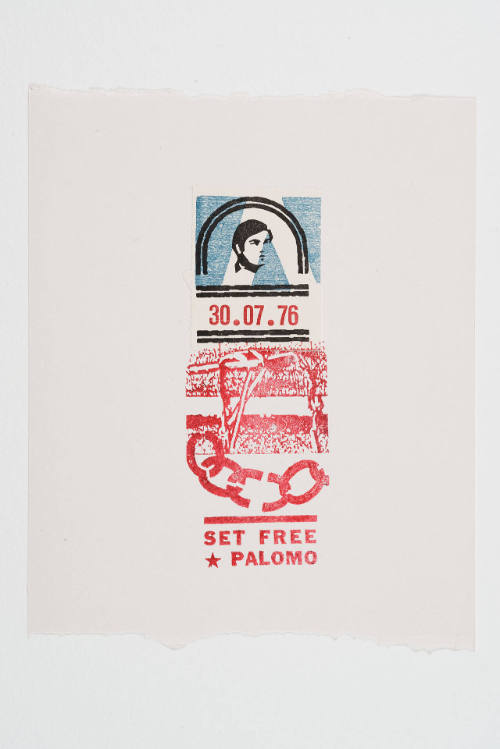

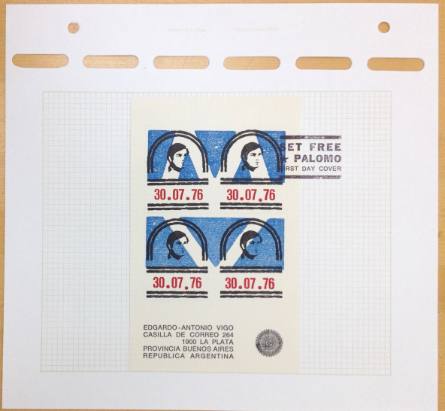

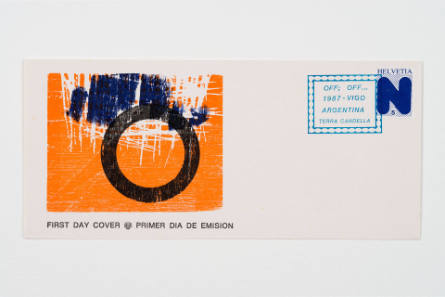

Set Free Palomo from Off; Off...

Primary

Edgardo Antonio Vigo

(La Plata, Argentina, 1928–1997)

NationalityArgentinean, South America

Date1987

MediumLinocut and rubber stamp on wove paper mounted on thick wove paper

DimensionsSheet: 7 11/16 × 6 1/4 in. (19.5 × 15.8 cm)

Credit LineBlanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of the artist, 1995.261.8

Rights Statement

Collection AreaPrints and Drawings

Object number1995.261.8/9

On View

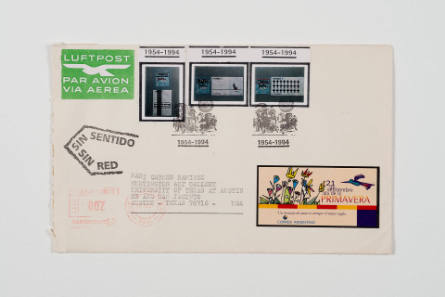

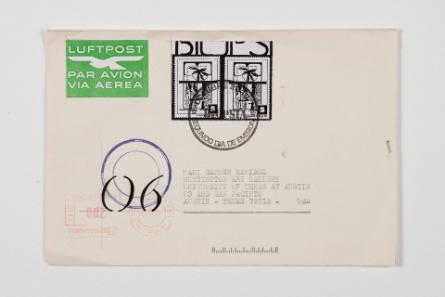

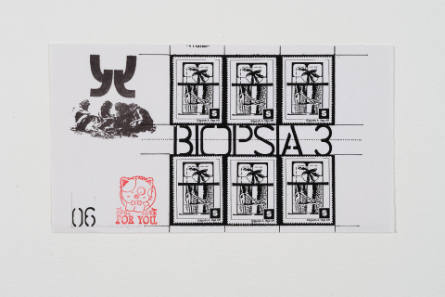

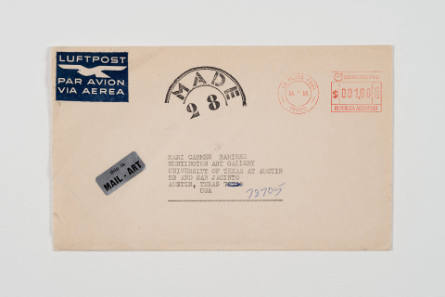

Not on viewIn the 1960s and 1970s, a series of military dictatorships seized power in Argentina and much of South America. In this period of political repression, the Argentine experimentalist Edgardo Antonio Vigo pioneered the use of Mail art to express dissent, spread information about the political situation, a covertly critique the government’s methods of censorship and control. Both magazines and Mail art rely on marginal, decentralized circuits of distribution outside of traditional institutions. Mail art, for example, concealed Vigo’s message while implicating the government in the delivery of its own critique, transforming the postal service into a conduit of subversion. Through his network, Vigo called for solidarity among artists in his network and encouraged artists around the world to take a political stance. In an essay he titled “Mail Art Statement,” he wrote that in the “Latin American ghetto,” the artist’s role is to fight against the “rising and suffocating fascist smog,” evoking the pervasive climate of terror and widespread violation of human rights.

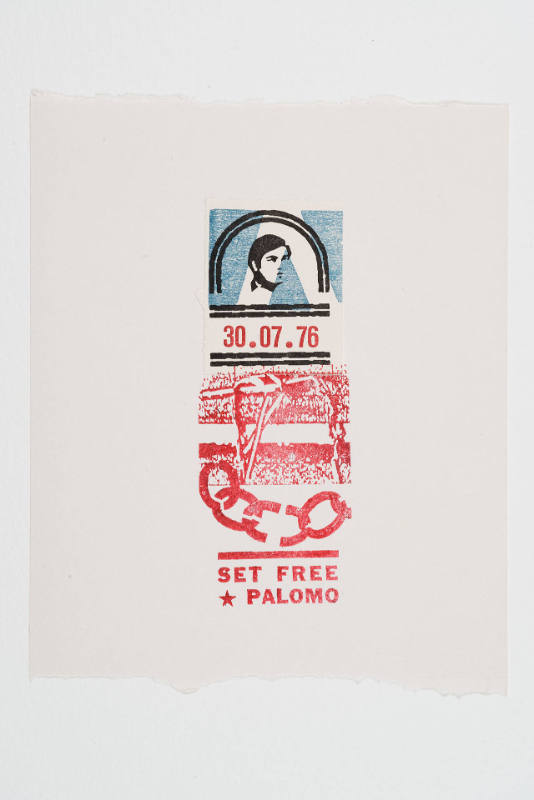

On July 30, 1976, Vigo’s son Abel Luis “Palomo” Vigo was disappeared by Argentina’s military. Palomo was never found; he joined the estimated thirty thousand people who disappeared during the Dirty War of 1976-83. In response, Vigo’s Mail art incorporated themes of censorship, incarceration, testimony, and grief over his missing son. Woodcut and rubber-stamp portraits of Palomo appear on many works from this period, accompanied by the date of his kidnapping or the slogan “set Palomo free.”

Edgardo Antonio Vigo

1995

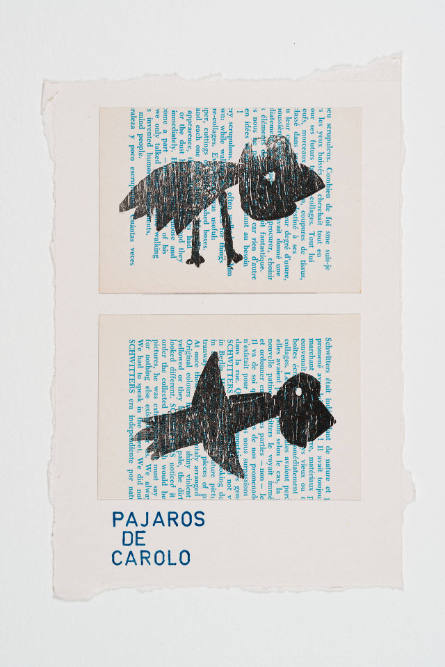

Edgardo Antonio Vigo

1995

Edgardo Antonio Vigo

1991

![Primer día de emisión [First Day Issue], from Múltiples Acumulados [Accumulated Multiples]](/internal/media/dispatcher/2630/thumbnail)