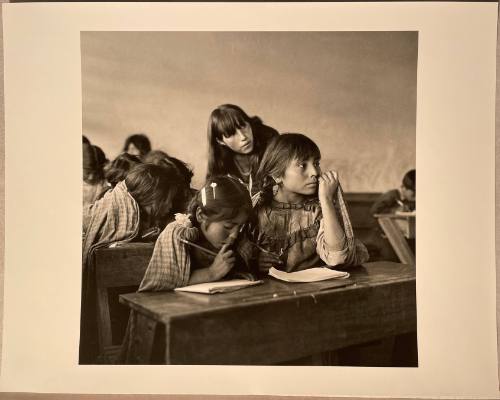

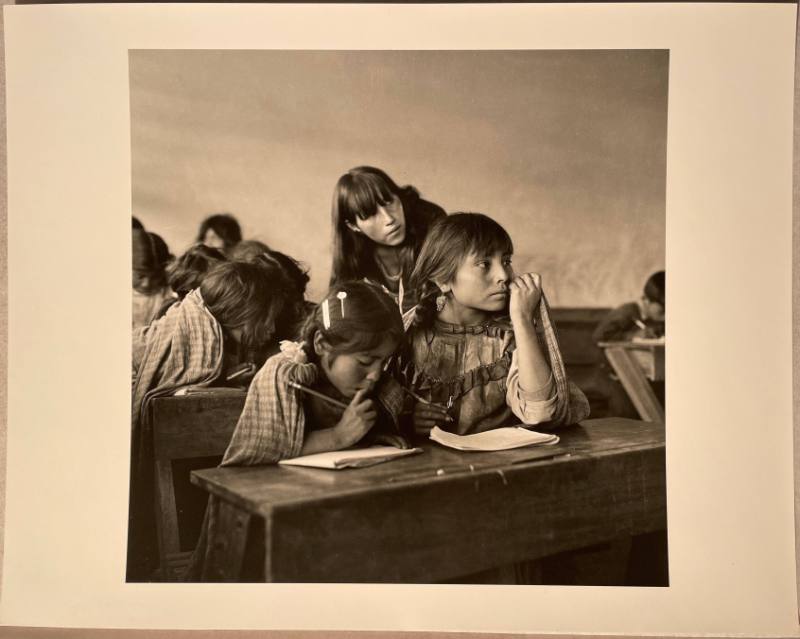

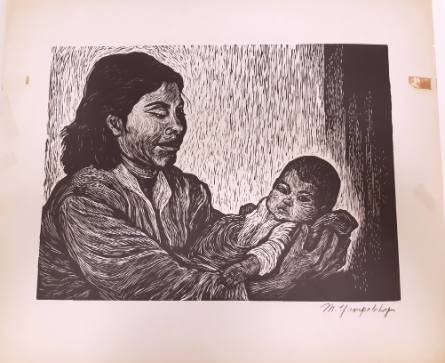

Escuela Mazahua [Mazahua School]

Image: 9 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (24.1 x 24.1 cm)

Mariana Yampolsky was a dual American and Mexican citizen. While attending Mexico’s Academy of San Carlos, the first art academy founded in the Americas, during the late 1940s, Yampolsky studied under photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo and gravitated toward capturing Mexican architecture and rural communities. Like Bravo and her husband Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Yampolsky used her photography to exalt the beauty of quotidian Mexican landscapes and the resilience of its people.

Escuela Mazahua is part of Yampolsky’s experience with the Mazahuan Indigenous people of central Mexico. Their communities face hurdles in receiving education beyond primary and secondary school due to extreme poverty, language barriers, and migrant work. In this scene, a teacher guides a Mazahua girls’ classroom. Teachers rarely remain in these schools long-term due to their remote locations and budget shortages, resulting in a lack of continuous education. In some cases, families restrict their daughters’ educations out of fear for their safety, due to dangerous anti-Indigenous sentiments, or for labor needs. Yampolsky's activist photography of Indigenous people seeks to reinforce their foundational place within the Mexican historical narrative, because, as she once stated, “I can’t conceive of art without a social context.”