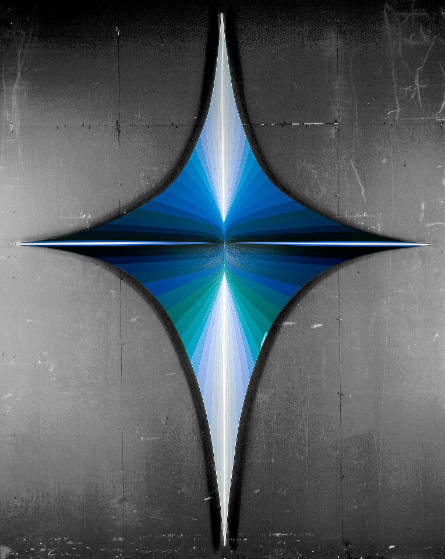

C-109

Primary

Tadasky

(Nagoya, Japan, 1935–Manhattan and Ellenville, New York, present)

NationalityAmerican, North America

Date1964

MediumAcrylic on canvas

DimensionsSight: 68 1/16 × 68 1/16 in. (172.8 × 172.8 cm)

Credit LineBlanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Mari and James A. Michener, 1991.329

Rights Statement

Collection AreaModern and Contemporary Art

Object number1991.329

On View

Not on viewCollection Highlight

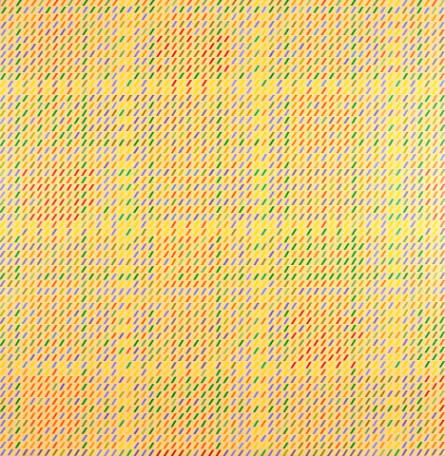

“It’s a little like staring at a turning record while trying to read the label,” wrote Jacqueline Barnitz in a review of Tadasky’s first one-person show in 1965. Barnitz, now a professor of art history at the University of Texas at Austin, aptly describes the work of Japanese-born, New York-based artist Tadasky. In the mid-1960s, Tadasky adopted the style that first brought him public recognition: circles composed of concentric rings that alternate between black and various combinations of complementary colors, such as the rusty orange-red and synthetic forest-green of C-109. It is the strong contrast between these colors that creates the illusion of movement noticed by Barnitz. Tadasky’s circles seem to wobble and spin, expanding out into the viewer’s space or, alternately, receding deep into the canvas. Visual agitation, accompanied by a sensation of physical disorientation, is the sum of an encounter with a painting like C-109.

Tadasky worked with the aid of a machine in the 1960s, which accounts in large part for his paintings’ precision, exactitude, and regularity. After placing a canvas on the machine’s flat surface, Tadasky would hold his brush over the support. The machine rotated at an even pace, allowing the artist to create concentric rings of uniform width. This method also had the result of expelling any trace of the artist’s unique touch from the painting.

In both form and effect, Tadasky’s circles lend themselves to a comparison with Marcel Duchamp’s Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics) (1920), Disks Bearing Spirals (1923), Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics) (1925), and Rotoreliefs (Optical Disks) (1935), which likewise sought to investigate the optical properties of abstract (specifically circular) motifs. What distinguishes Duchamp from Tadasky is that the latter used abstract motifs to generate the impression of movement—what we might think of as virtual movement—while the former set his abstract motifs in motion electrically. Duchamp exerted a profound influence on postwar American artists, particularly after his 1963 retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum, which was responsible for prompting renewed interest in the artist’s work.

Exhibitions